Από το μπλογκ της Glenna Gordon (ως Scarlett Lion)

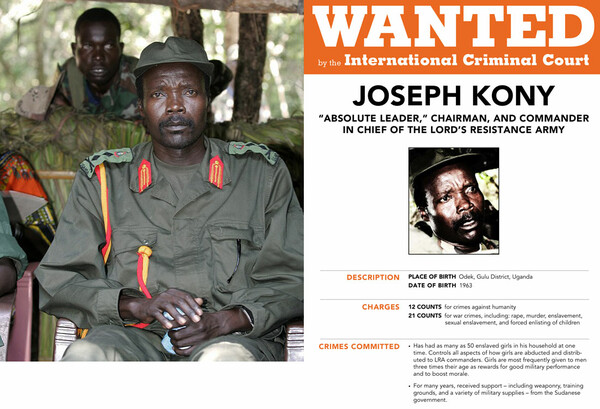

Why Invisible Children can’t explain away this photo

The now infamous photo of the Invisible Children film makers tells several different stories. Though I originally questioned whether or not I’d have wanted the image released if I had an option, I now realize that the release was both inevitable and ultimately effective.

The first and most obvious image that this story tells is that these guys are posing to look cool, which in turn makes them look terrible. This is what most people who see the photo think. That’s certainly what I thought when I took the photo back in 2008, and that’s certainly how it’s being used in the media now for the most part.

But, it also does this other thing — it reinforces Jason, Bobby and Laren’s bad-ass-ness, making them look good even while it undermines their authority. It screams, look how cool we are! Check us out on the Sudan-Congo border! They are awesome dudes who are taking care of business. This appeals to the many young people who want to be bad-asses and pose like Rambo.

Ultimately though, this is a photograph about privilege: they are outsiders, playing solider, involved in a conflict that they can leave and where others are not playing.

And they know that. In fact, they know that so well that they used that photo as the banner image on their page responding to criticism – trying to re-appropriate it and snuffing out its power by making it their own.

A story told by Jason Russell: Let me start by saying that that photo was a bad idea. We were young and we got caught up in the moment. It was never meant to reflect on the organization. The photo of Bobby, Laren and I with the guns was taken in an LRA camp in DRC during the 2008 Juba Peace Talks. We were there to see Joseph Kony come to the table to sign the Final Peace Agreement. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) was surrounding our camp for protection since Sudan was mediating the peace talks. We wanted to talk to them and film them and get their perspective. And because Bobby, Laren and I are friends and had been doing this for 5 years, we thought it would be funny to bring back to our friends and family a joke photo. You know, “Haha – they have bazookas in their hands but they’re actually fighting for peace.” The ironic thing about this photo is that I HATE guns. I always have. Back in 2008 I wanted this war to end, like we all did, peacefully, through peace talks. But Kony was not interested in that; he kept killing. And we still don’t want war. We don’t want him killed and we don’t want bombs dropped. We want him alive and captured and brought to justice

But, for all of the people who do feel uncomfortable with Invisible Children’s slick message and questionable overtones, there’s a photograph floating around the Internet that confirms those fears. It makes people doubt IC, despite their best efforts to re-appropriate it, to explain it away.

A friend called it “the photo that is the best visual indictment taking down the Invisible Children.” I hadn’t thought of the image as that until she said it. Many photographers hope that our images can change something, that our images can make people doubt their assumptions and reconsider easy answers.

And I realize now that at least this one has.

Copyright Glenna Gordon

Vice wrote a post with a valid question: “Should I donate money to Invisible Children?” and they used my photo without having requested permission. Had they contacted me, I would have been very hesitant.

I explained to Vice:

While I agree that the point of the article is to raise questions — a practice I support — the photograph, even when making that point, continues to perpetuate misinformation and to mythologize the film makers as bad asses, a practice I do not support. While the photo can be used to criticize them, there are a whole lot of teenagers in Iowa thinking to themselves right now, “Awesome!”

But, here we are, the photo is up and all over the internetz, and Vice has agreed to add a caption for some context, attribution, etc.

My doubts about this photo persist. I have put up other photographs of white people doing different stuff in Africa before. And, at a different moment in my thinking on these things I did share this photo with Wronging Rights.

Recently, though, I’ve hoped to explore the idea of the privilege outsiders are granted with nuance and a soft touch that leaves room for ambiguity. For more on this, please read my post “On bias, subjectivity, and deeply personal photography.”

This photo doesn’t do that — it just contributes to the stereotypes of kids messing stuff up by showing the worst of the worst and showing it without context. And worse yet, it adds to the Invisible Children bad ass mythology even while attempting to cast doubt on their practices.

So, some context: Sudan-Congo border, April 2008. We’re all bored out of our minds waiting for endlessly stalled peace talks to resume. Invisible Children dudes have some fun by posing with SPLA soldiers. I uncomfortably photograph them having said amount of fun. Later, I worked with a colleague to try and publish a story about what we saw as their questionable practices, but we couldn’t get a publication to bite. Now, perhaps that’d be different, and at the end of the day, I do hope that all of this can make us look at Invisible Children with a more critical stance.

Obama Takes on the LRΑ

Από το περιοδικό Foreign Affairs.

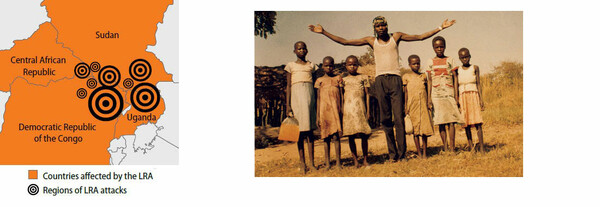

A rare photo of Kony from 2008. Read more of Foreign Affairs' coverage on Africa, sign up for our newsletter, or subscribe.

As a United Nations staffer said recently, while attending an internal briefing on the Lord's Resistance Army, the violent central African rebel group, earlier this fall, "November is LRA month." Indeed, the LRA and its notorious leader, Joseph Kony, are suddenly everywhere: several non-governmental organizations have held advocacy briefings about it at the United Nations, and the Security Council met on November 14 to discuss them. Meanwhile, journalists in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere are suddenly seized with the mission of finding out what is really happening on the ground in central Africa.

Two events underlie the renewed interest. First, in October, U.S. President Barack Obama announced that he would be sending "combat-equipped troops" on a kill-or-capture mission to take out Kony. Second, on November 2, Hollywood released Machine Gun Preacher, a movie billed as the true story of an American missionary's Rambo-esque crusade against the LRA. Curiosity about the events depicted in the film will soon subside, if early reviews are anything to go by, but Obama's decision, which he pitched to the American public as a dramatic new development, is another matter.

The LRA conflict goes back to the late 1980s. After toppling the regime of Tito Okello, the victorious forces of Uganda's new president, Yoweri Museveni, sought to impose his authority on the Acholi population in northern Uganda, which had been closely associated with Okello. A diverse range of resistance groups emerged at that time; all were eventually defeated, except for the LRA, which proved more resilient than anyone might have imagined. In the decades that followed, the outside world largely looked the other way as Uganda's north sunk into violence and deprivation. That changed in the early 2000s, when images of thousands of children taking refuge in the town of Gulu, Uganda, first hit mainstream television. Various celebrities began to speak out about the war, mostly focusing on shocking incidents associated with Kony's rebels; the Ugandan government's aggressive counterinsurgency measures, however, were shocking as well. For example, the government forced the region's population to relocate into what were effectively concentration camps. There, they were poorly protected from attacks, and faced dreadful living conditions. A study carried out under the auspices of the World Health Organization in 2005 found that there were 1000 excess deaths per week in the Acholi region.

Growing recognition of the scale of the crisis within the humanitarian system was coupled with occasional intense periods of media attention that brought awareness to a wider audience. Media reports mostly covered LRA atrocities and were prompted by particular events, such as when, in 2005, the newly created International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants -- its first ever -- for the LRA's top commanders; when Kony announced his interest in peace negotiations in 2006; and when he repeatedly failed to sign the subsequent agreement in 2008. There has been rather less media concern about events after that failure.

Obama's apparent sudden escalation of U.S. engagement in Uganda, then, came as quite a surprise. His announcement did not publicize the fact that U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) has had an unspecified number of soldiers deployed in the area to assist the Ugandan army for years. In late 2008, AFRICOM was even involved in a military push to take out the LRA once and for all. It is easy to understand why Operation Lightning Thunder, the mission aimed at capturing or killing Kony at his main base in Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, goes unmentioned. Kony and his commanders had vacated the area well in advance. The mission was beset with other problems, too. U.S. military personnel helped in planning, but they appear to have held back when it came time for carrying those plans through. Meanwhile, Ugandan military officers lacked the necessary training and equipment, and in some cases ignored U.S. direction.

Operation Lighting Thunder, and other such missions to fight the LRA in the Central African Republic and in southern Sudan, served mostly to kill efforts to keep beleaguered peace talks going. And, far from neutralizing the LRA, they prompted a strategically effective and ferocious response. In January and February 2009, the LRA abducted around 700 people, including an estimated 500 children, and killed almost 1,000. At present, the LRA operates in an area as big as France, stretching from southern Darfur to parts of South Sudan and northern Congo. All this, and the plight of local populations, who are caught between a rebel group with nothing to lose and armies that have not prioritized civilian protection, has been mostly overlooked.

The reactions to Obama's recent statement underscore how little Americans -- journalists included -- know about the United States' involvement in Uganda. In the rush to say something, newspapers and television shows seem to have largely based their material on the somewhat confused Wikipedia entry on the LRA. That may be where the conservative talk radio host Rush Limbaugh found what he called the "Lord's Resistance Army objectives," which appear on the site and which he used in a bizarre defense of Kony's group on U.S. television. (He apparently supposed that the LRA is a group of Christians fighting Muslims in Sudan.) Journalists seemed equally misinformed. Once initial inquiries along the lines of "Who are the LRA?" and "What do they want?" are out the way, the most common questions are "Why intervene now?" and "What is in it for the United States?"

Obama claimed that he decided to act because it "furthers U.S. national security interests and foreign policy." Yet it is not entirely clear how that could be true, since Kony and the LRA have not targeted Americans or American interests and are not capable of overthrowing an allied government. It is worth noting that support for the Ugandan military does coincide with the broad thrust of the Obama administration's African alliances and strategic agenda. The Ugandan army's help in Somalia through AMISOM was much appreciated, and Uganda is paying a considerable price for it. The number of its own troops killed has reached several hundred, according to some sources, and al Shabaab has launched attacks on Kampala, Uganda's capital. So the U.S. mission might be viewed as a kind of payback for Uganda's cooperation in the war on terror. In addition, geologists recently discovered oil in and around Lake Albert -- another reason for closer cooperation and for stabilizing the area. But even so, for obvious reasons it is unusual to publicize the movements of special forces in advance of their deployment. To a cynical observer, then, Obama's announcement seems to have been aimed at achieving some other goal.

During the past decade, U.S.-based activists concerned about the LRA have successfully, if quietly, pressured the George W. Bush and Obama administrations to take a side in the fight between the LRA and the Ugandan government. Among the most influential of advocacy groups focusing specifically on the LRA are the Enough project, the Resolve campaign, the Canadian-based group GuluWalk, and the media-oriented group Invisible Children. Older agencies, from Human Rights Watch to World Vision, have also been involved. In their campaigns, such organizations have manipulated facts for strategic purposes, exaggerating the scale of LRA abductions and murders and emphasizing the LRA's use of innocent children as soldiers, and portraying Kony -- a brutal man, to be sure -- as uniquely awful, a Kurtz-like embodiment of evil. They rarely refer to the Ugandan government atrocities or those of Sudan's People's Liberation Army, such as attacks against civilians or looting of civilian homes and businesses, or the complicated regional politics fueling the conflict.

In 2001 U.S. President George W. Bush placed the LRA on the U.S. Terrorist Exclusion List, a list of groups involved in "terrorist activity" whose members are banned from entering the country. Six years later, after activists camped out for eleven days in front of the house of Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn, who had objected to U.S. legislation against the LRA due to funding concerns, Obama signed into law the Lord's Resistance Army Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act, which called for "increased, comprehensive U.S. efforts to help mitigate and eliminate the threat posed by the LRA to civilians and regional stability," and requires regular official reporting to Congress on how the fight against the LRA is proceeding.

Predictably, activists have claimed Obama's decision to send in troops as a victory, or, more specifically, as "a huge victory for the hundreds of thousands of young Americans who have been lobbying Washington to take action." And, in any event, for congressmen wanting to score a few human rights points with their constituents, making statements opposing a violent faction in Africa is an easy stance to take. Perhaps, too, the administration estimated that potential U.S. losses would be minimal, and that Kony would be a good addition to the list of international thugs removed during Obama's time in office.

So domestic political agendas, which at least did not conflict with broad U.S. strategic interests, are the most probable explanations for Obama's decision. It will be a big miscalculation if the operation does not go well.

There are some reasons for optimism. The U.S. military has gathered strong evidence about Kony's whereabouts in the last few months. Greater numbers of surveillance flights over LRA-afflicted areas are said to have pinpointed Kony's position in the Central African Republic. Washington also has a better understanding of the Ugandan military's strengths and weaknesses. Obama stated explicitly that, this time, U.S. forces would be available to help carry through the mission. If they are deployed effectively, they could indeed have an impact.

Even so, it is hard to set aside fears that the new effort will be no more than a repeat of previous ones. Such an expectation has certainly been expressed by many of the region's religious leaders, who openly oppose U.S. engagement. And reports about growing fatigue within the Ugandan army are alarming. Of the more than 4,000 Ugandan troops that were originally sent to LRA-affected areas, less than 2,000 remain. They are operating in three different countries, leaving very limited capacity on the ground. To just break even with those losses, Obama would have to send far more troops than the planned 100. Any high expectations in Uganda for the new U.S. soldiers, meanwhile, where dashed when information trickled out of Washington that the troops would probably stay in Kampala and give advice, rather than go into combat.

According to local sources, the LRA has already announced that it is ready for a fight, and is said to have called on its members to gather and "celebrate" Christmas and New Year's -- a reference to the string of violent retaliatory attacks it carried out on December 25, 2008, and in the days that followed. Increasingly fearful local populations have started to create their own protection forces. Leaving aside the general problems associated with the militarization of civilian societies, it is unrealistic to believe that such units will be able to respond effectively to LRA retaliations. And, although the United States has committed itself to protecting civilians in Uganda, it appears to have no plans to do so, nor did it consult with UN forces in the area. This is rather baffling, since much of the pressure on the administration comes from groups asking it to do exactly that: protect civilians. There also seems to be no consideration of the broader implications of strengthening the national army of Museveni, who is apt at using those forces to maintain power, and of the long-term plague of the continued militarization of Central Africa.

Even if all these concerns could be set aside -- assume, for a moment, that the military intelligence is good; lessons of the past have been learned; mechanisms to protect the population will be put in place; the armies of Uganda, Congo, and South Sudan are controlled; and U.S. special forces are able to find and kill Kony -- would the effort bring peace? The answer is probably not.

To be sure, Kony's death would be welcomed at home and abroad. But the mission would not be entirely satisfactory if troops killed him instead of bringing him to trial at the International Criminal Court. Only there could his crimes -- and those of others -- be examined in detail. The United States has not, of course, ratified the statute of the ICC, and did Obama not make reference to trying to arrest Kony in his announcement. If U.S. armed forces do engage in combat, it will be revealing to see whether they facilitate the LRA leader's capture or his killing.

Beyond the ins and outs of dealing with Kony, the political challenges in the region are simply too massive for Obama's new operation to yield much fruit. The violence in Uganda, Congo, and South Sudan has been the most devastating -- anywhere in the world -- since the mid-1990s. Even conservative estimates place the death toll in the millions. And the LRA is, in fact, a relatively small player in all of this -- as much a symptom as a cause of the endemic violence. If Kony is removed, LRA fighters will join other groups or act independently. Civilians will remain exposed to atrocities committed by other armed groups, including their own national armies.

Until the underlying problem -- the region's poor governance -- is adequately dealt with, there will be no sustainable peace. Seriously addressing the suffering of central Africans would require engagement of a much larger order. A huge deployment of peacekeeping troops with a clearly recognized legal mandate would have to be part of it. Those forces would need to be highly trained, have an effective command structure, be closely monitored, and be appropriately equipped with sophisticated surveillance equipment and helicopters, among other things. It would require a long-term commitment and would be targeted not only at chasing the LRA. Moreover, it would make the protection of the local populations a key priority. Finally, the deployment of such a force would need to have emerged from concerted efforts in international diplomacy -- including with the African Union, the United Nations, the ICC, and governments in the region -- not as a knee-jerk reaction to the most recent media splash.

Such a mission is unlikely to come about. Nonetheless, it underlines the point that a superficial focus on the activities of one man and a few of his commanders largely sidesteps the point. Kony and his colleagues lead a dreadful but relatively small organization that punches above its weight. If achieving stability and relative prosperity in this blighted region of Africa is the real objective, devoting the month of November to the LRA will obviously not be anything like enough.

Should I Donate Money to Kony 2012 or Not?

So you probably woke up this morning to discover that something called Kony 2012 had taken over the internet. In case you haven't worked it out yet, Kony 2012 is a film produced by the charity Invisible Children, raising awareness about the child soldiers of Uganda. Since it was released on YouTube on March 5, it's been viewed several million times. Here it is:

And that's good, right? Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army abduct children and convert them into murderers. They've been doing it for years and it's good that someone's trying to raise Kony's profile so that American politicians might be forced into doing something about this endless tragedy, right?

Well, it's more complex than that. You might have noticed that when ANYTHING happens on the internet, there's always someone waiting to crap all over it. Sure, quite often they're crapping all over teenage girls by calling them sluts, but every now and then they'll take a big shit on something that deserves it, like SOPA. Basically, if there's something humans like, there'll be a bunch of other humans who hate it.

Well, predictably, some are shitting on Kony 2012. I'm sure those behind the film and the charity would just brush criticism off as thoughtless cynicism. After all, once something is so big that Rihanna's tweeting about it, some people are going to be suspicious, jealous, and try to ruin it, no matter what. Some chumps are just contrarians, right?

That said, here are some of the major criticisms of Invisible Children and Kony 2012.

Criticism #1: Invisible Children is a financially questionable organization.

These figures have been circulating.

It's impossible to understand everything about Invisible Children's motives by analyzing these figures alone. Eighty-nine grand does seem like a sweet wage, but does that matter so much? That its expenses are high compared to its revenue isn't too surprising, either. The Kony 2012 manifesto is to raise awareness. People are donating to raise the profile of the Ugandan plight, and, overnight, thanks to a film on YouTube, millions more people were made aware of it. Success, then.

Criticism #2: Invisible Children is not financially accountable.

According to some of the internet, Invisible Children refuses to co-operate with the Better Business Bureau—an organization that investigates the ethical nature of companies.

Also, according to the Charity Navigator (a website I was unaware of until today), Invisible Children is not particularly transparent.

Criticism #3: Invisible Children lies.

According to an article published by the Council on Foreign Affairs:

In their campaigns, such organizations [as Invisible Children] have manipulated facts for strategic purposes, exaggerating the scale of LRA abductions and murders and emphasizing the LRA's use of innocent children as soldiers, and portraying Kony—a brutal man, to be sure—as uniquely awful, a Kurtz-like embodiment of evil.

Criticism #4: Invisible Children wants to flood Uganda with weapons.

OK... This is a picture of Jason Russell, Bobby Bailey, and Laren Poole, the filmmakers who founded Invisible Children and made Kony 2012.

Photo by Glenna Gordon

Oh dear. Bad idea, guys. I mean, don't get me wrong, if VICE ever wants to send me to somewhere like Congo, the first thing I'll do is get a Facebook picture of me with a gun. But then I'm not lobbying for the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (who, I'm informed, have been accused of rape and looting) to be armed by America.

I'm not an expert, but isn't the history of arming one group of guys to go and kill another group of guys in some far away country nearly always a really shitty idea? Doesn't it lead to ethnic cleansing, extremism, revenge, tribal conflict, and general misery? Maybe not. As I say, I'm no expert.

Criticism #5: Invisible Children is staffed by douchebags.

Now when I first watched the Kony 2012 video, there was a horrible pang of self-knowledge as I finally grasped quite how shallow I am. I found it impossible to completely overlook the smug indie-ness of it all. It reminded me of a manipulative technology advert, or the Kings of Leon video where they party with black families, or the 30 Seconds to Mars video where all the kids talk about how Jared Leto's music saved their lives. I mean, watch the first few seconds of this again. It's pompous twaddle with no relevance to fucking anything.

However, the central message—stop this cunt Kony killing and raping innocent children in their thousands—is a very powerful one. So I looked beyond my snobbery.

Maybe I shouldn't have. Chris Blattman, who's an Assistant Professor of Political Science and Economics at Yale, wrote this blog about Invisible Children, effectively just calling them twats. He starts by dissing their "hipster tie" and cowboy hats, before moving on to accuse them of being post-colonialists.

................................................................

So, now I'm in a bit of a quandary. I'm worried that the real reason I went to seek out the downsides of the Kony 2012 phenomenon was simply because I'm a snob who enjoys bursting people's bubbles, and because I find the promotional film they made for it embarrassingly produced. What a horrible reason that would be to ignore a charity.

The film Kony 2012 began because the filmmakers went to Uganda and met a young boy so traumatized by his experiences that he was contemplating suicide. Confronted with the grotesque reality of the atrocities, the Western filmmakers did what I hope I'd do, and resolved to help. No matter what. With that in mind, does it matter if they get paid well? Does it matter if they massage the facts? Does it matter that their charity isn't completely accountable? Does is matter that they're naive prats who think it's the white man's job to save Africa? Or is that all just pompous hypothesizing by Westerners with enough freedom, information, and education to look down on a simple, kind act?

Isn't it better to just stop criticizing and start helping children in need? Or is that the kind of blind interventionist attitude that throws countries like Afghanistan into very, very long wars?

I don't bloody know. Soz.

(Thanks to all the blogs and people on reddit that I ripped off, BTW.)

Follow Alex on Twitter: @terriblesoup

To get involved with Kony 2012, click here.

For more information about why you SHOULDN'T donate to Kony 2012, click here.

If you're in the mood for more horrible tales about people getting hurt in Central and Eastern Africa this lunchtime, why not check out these:

5 days ago

"It was a joke !"

Charity’s Contras: Invisible Children (Kony 2012)’s Support of Death Squads, Child Soldiers and Genocide (από την εφημερίδα The red Phoenix).

Despite their calls to arrest Joseph Kony, leader of the Ugandan theocratic guerrilla group Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and a wanted war criminal responsible for horrendous atrocities, the makers of the viral video “Kony 2012″ from the Invisible Children campaign have been heavily criticized for funding death squads themselves.

The above image is a picture of the founders of Invisible Children posing with members of the South Sudan Peoples Liberation Army. Invisible Children funds the SPLA in South Sudan and the U.S.-backed Ugandan dictatorship, both of which are guilty of war crimes, genocide, and mass rape. This campaign claims to want to bring war criminal Joseph Kony to justice, but ignores the similar atrocities committed by the Ugandan army and Sudan People’s Liberation Army.

America and China competed for the African oil state of Sudan a few years ago. Now there is the U.S. and Zionist puppet state of South Sudan with oil deals to the U.S. and Israel. During that time there was the “Save Darfur” campaign. Now China and the U.S. are competing for economic control of Uganda, including oil, and there is “Kony 2012.” Coincidence?

The natural resources and massive economic potential to be made by multinationals in Africa and Uganda, 100 US troops deployed to Uganda months earlier and China buying up all of Africa, including much capital in Uganda, are enticing for Western imperialism.

Invisible Children’s founders are profiting off of imperialism and funding death squads inside Africa.