The queues outside the Acropolis Museum are reminiscent of pre-Covid times, the General Director of the museum is looking at the people enjoying their visit while the archaeologists are giving guided tours as part of the action “Hidden Stories of the diaspora” on the adventures of the fragments and other antiquities from the Acropolis that today are scattered in various European museums.

Nikolaos Stampolidis welcomes me and immediately leads me to the third floor, where the permanent reunification of the famous Fagan fragment from the A. Salinas Museum in Palermo is now completed. The piece depicts the lower limbs of the goddess Artemis, who is watching the Panathenaic procession approaching the great temple, and is located in the east frieze of the Parthenon, in the Acropolis Museum.

This permanent first reunification comes just days after Jonathan Williams, deputy director of the British Museum, made inflammatory statements at the meeting of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Commission (ICPRCP), saying that most of the sculptures removed by Lord Elgin were found “in the rubble” around the monument and that Greece’s desire to see the Parthenon complete is impossible to realise, as a large part of it had been destroyed long before Elgin arrived in Greece, creating quite a tension between the Greek and British sides. In our meeting, I asked Prof. Stampolidis to look back at the history of the destruction and talk about all the arguments of the British and how they were overturned at the UNESCO meeting.

When I visited the British Museum, to join the piece from Kos with the slab Nr 1022 from the Amazonomachy frieze of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, I was able to see the frieze plaques of the Parthenon and I found that not all of them were sawed off, some were broken off with a chisel.

— The British know how the sculptures were removed and vandalized. Mr. Williams knows it too, doesn’t he?

Don’t think they don’t know we’re in the right. That’s why they are sometimes in a very difficult position, because when you corner someone and they have no more arguments, they bring up old ones that have been refuted. I’m a man who likes to put himself in the other’s shoes, so I think, maybe, Williams was being pressured, therefore he couldn’t have acted differently.

— You mean to tell me that Williams has been put in a very difficult position.

Of course, that’s why he used an argument that is undeniably refuted, i.e. that not all the sculptures were on the temple and were torn down by Elgin, but that there were some around the monument.

— Why do you think this argument has resurfaced? I mean the statement that triggered a new round of discussions.

Because it could, in the opinion of some, prove that Elgin did not destroy the sculptures. That is, that Elgin’s associates didn’t get up on the temple and saw all the sculptures off and break them, but that there were some on the ground that were already broken.

— What was the situation on the Acropolis in 1801?

At that time it was built on and smaller or larger parts of the temple were inhabited − I am not only talking about the architectural parts but also about stones with reliefs, some of which were embedded in buildings. They were what archaeologists call material in second and third use. Some of them had come from the destruction caused by the Morosini explosion in 1687. When I visited the British Museum, to join the piece from Kos with the slab Nr 1022 from the Amazonomachy frieze of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, I was able to see the frieze plaques of the Parthenon and I found that not all of them were sawed off, some were broken off with a chisel.

— So they weren’t pulled out of the ground but were hammered off?

Even the pieces that were on the ground and had reliefs on them were vandalized, by breaking them with a hammer and chisel, to lighten them in bulk and weight, so that they could be send to England on the sailing ships of that time. I must tell you that those of us who study both ancient and modern sculpture know that when you violently strike a piece of marble with a hammer and chisel its veins can split and thus you may break off pieces you do not want to harm, that is, reliefs or sculptured surfaces.

— Which is what happened?

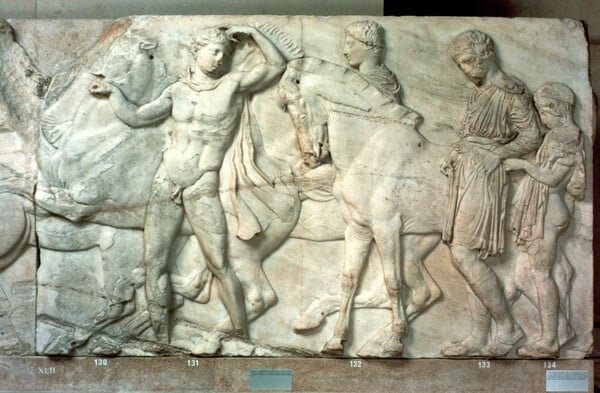

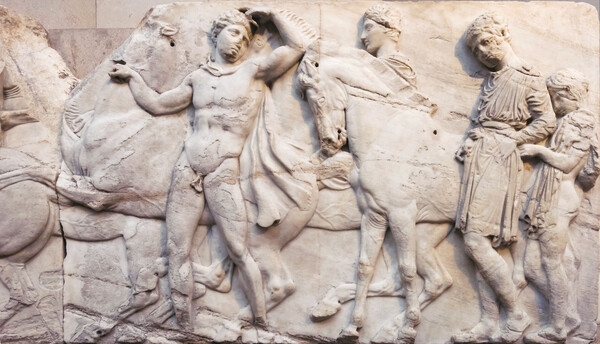

Of course. If you look carefully at the whole frieze, you will see that, in addition to the sawing, there are scrapings, thinning, in the volume of the stones. The Parthenon frieze is not composed of slabs 14-23 centimetres thick, like those hung on the walls of the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum. Its stones are approximately 53 to 65 centimetres thick. Therefore, by breaking and cutting away the sculptures, Elgin left, if he didn’t demolish it himself, the rest of the block to collapse. Consider that the frieze is on the wall of the temple’s cella, at a height of ten to twelve metres. On top of it there was a decorative finial piece. In order to be able to remove the frieze stones, he would tear off the finial piece, throw it down, saw off the piece he was interested in, and the rest would either fall off, breaking, or stay up, but collapse after a while.

— What proof do we have of this?

Clarke writes that one day in September 1802, Elgin’s collaborators wanting to remove a metope depicting a Centaur −metopes come sliding between the triglyphs− he tried to lift it, and a piece of the building from the superstructure of the temple, the massive Pentelic marbles, came crashing down with a terrible rumble because of the detaching machinery. Their shattered pieces were scattered among the ruins. If my colleague meant that these are the ones fallen down, what can I say!

The state of the Parthenon in the second half of the eighteenth century can be seen in the drawings and lithographs of the period, which are irrefutable witnesses. It is clear what kind of destruction Elgin’s associates wrought on the sculptures. But, you know, the best evidence of the destruction of the stones is to “read” it through the marks on them, for anyone who knows how to read them. But there is also written evidence, even from the letters of Elgin’s associate Lusieri, who asks him for saws of various sizes so that he can cut the marbles himself. At one point in his letters he writes “I am forced to become a barbarian”, aware that what he is doing is barbaric.

— Can you give me an example? When you go to the British Museum, do you understand what it is that you’re looking at?

The Nereid Monument in the British Museum is rendered almost in its entirety, with the pedestal, the columns, the statues between the columns, its pediment, like the Pergamon altar in Berlin. These, in a way, are readable monuments. In contrast, when one goes to the Duveen Gallery to admire the Parthenon Sculptures, one honestly doesn’t understand what they are, only the aesthetics, the beauty and the glow that they emit. One looks at beautiful things lined up, like paintings hanging on the wall; you don’t even understand where the sculptures came from, from which temple, etc. From a museological point of view, it is a flawed exhibition. Duveen built the room according to the dimensions of the sculptures that were purchased by Elgin to be displayed in this way. That’s it!

— So when we see them, we do not get a sense of the monument, the place and the light.

No, nor of the environment that gave birth to them. A museum that prides itself on being educational and encyclopedic in nature has unfortunately not made sure it depicts the truth, beyond the aesthetics of the “glowing” sculptures. It is a deceiving image one gets.

— It’s not like that in the Acropolis Museum?

No, because this new “temple”, the Acropolis Museum, was built to protect the sculptures from the weather conditions and air pollution. The Parthenon Hall on the third floor is the size of the actual temple, and the monument itself is directly opposite it on the “holly” rock. Again, I wish we could put them in their place, up on the Acropolis. But they have to be protected, so this museum was built for it.

— What image of the sculptures do we get in the Acropolis Museum?

Here the modern visitor can get the real picture. On one of the long sides there are seventeen columns, as in the Parthenon, on which the visitor sees in the foreground the metopes that have survived. The frieze is 160 m. long and the blocks surround the upper part of the walls of the cella, of course at a height where the viewer can enjoy it. Finally, the sculptures of the west and east pediments are placed in such a way that they are in dialogue with the monument. And, of course, the light of violet-crowned Athens, as Pindar says, the eternal Attic light, which really bathes the figures of the Panathenaic procession, falls on all of them. One might say that the pediments need to be a little higher or that there should be a background to project the sculptures on. But these are opinions and details that can be corrected, if needed.

— Jonathan Williams says the monument will never be complete.

Some pieces may be gone forever, but what monument has remained unscathed by vandalism or the ravages of time? None. But that’s all the more reason for the sculptures to come back and be reunited; those that are in the British Museum and those that are elsewhere should come back to their native place in order to minimise the gap created by history, time and decay.

— Do you think the British Museum won’t give away the sculptures because they are its most valuable exhibit?

There is no doubt that it is a most valuable exhibit. But it is a matter of stubbornness, in my opinion. Not stubbornness of the British people, or of those who serve the British Museum, or of any government. It is a stubbornness of certain people or circles who for some reason feel they have the right to hold the sculptures captive.

— They have talked about pollution and poor maintenance conditions.

All the arguments have been refuted over time, with evidence. When the New Acropolis Museum was not ready and everything was displayed in the small museum on the rock of the Acropolis, the constant argument was “if we give them to Athens, where will you put them?” When this museum was built to house the sculptures, that argument was shot down. They said “there’s too much pollution in Athens”, as if there isn’t pollution in London. That argument was refuted too. And let’s not forget that they had coal burning stoves inside the Duveen Gallery some decades ago. When the architectural sculptures were moved here, to the New Acropolis Museum, and underwent cleaning without any damage, without the wire brushes and acids that had been used in the British Museum, that argument was also abandoned.

— Let’s talk about the cleaning, which has been done in the wrong way, and the “request” for whiteness of that time.

We have read all of that. In the interwar period, in 1937-38, as Forsdyke, at the time director of the British Museum, reports, a disastrous cleaning was carried out without permission because Lord Duveen wanted the sculptures to be bright white. We read that archaeologists and guards told him they were “scrubbing the marbles”. According to the fashion of the time, they had to be white to be exhibited in the room, and these sculptures had colors and unbelievable details.

— And those details were scraped off?

Of course, some details like color or traces of color were gone forever.

— Did the international scientific community react, back in those times?

Clearly. An example is Professor Cesare Brandi. There have always been reactions, even as far back as 1816, when Elgin wanted to sell the sculptures. At least thirty MPs condemned the act, saying it was an outrage. Initially Elgin wanted to keep them in his house, resulting, as is well known, to damage from humidity and poor conditions, which added to that caused by the shipwreck of “Mentor” that carried them. Of course there were also reactions from the Greek state, already after the time of King Otto, but the British answer was always negative or the case was stopped in other ways. Even the argument about the fallen pieces has been around for a long time, but it is refuted by what I have already told you, that they too have been demonstrably damaged, in order to lighten their volume and weight, and therefore some of the reliefs themselves have been damaged.

— Are they claiming they can keep the fallen ones?

Perhaps, because they assume that these were not vandalized by Elgin, which of course isn’t true. There are thirty-four fallen ones and twenty-two sawed off from the temple. The fallen ones, I stress again, were also vandalized. So, it is not only the act of stripping them from the Parthenon, of which we have evidence, but also Clarke’s description and Lusieri’s letter of 5 January 1802 about the sawing. Robbed from the temple itself or found fallen, the dismemberment and vandalism of the Parthenon sculptures is a fact.

— So since 1801 we have a continuous act of destruction that lasts until when?

Until 1810. Consider that even the Ottoman authority, the voivode of Athens, after seeing that the sculptures were being destroyed, said “enough”. Also, I must add here once again that there was no authorization (firman) from the Sultan. Sir Adair, who served as the UK ambassador to Constantinople, reports that the Ottoman officials in the City flatly denied that Elgin had any right to take the marbles. This was when most of the sculptures were in Athens and the voivode was still seeking an export permission from the Sublime Porte. William St. Clair writes that officials replied that Elgin had never obtained permission to remove antiquities from the Acropolis and had no property rights over them. Permission for the second part of the sculptures that Lusieri had torn away was granted in 1810, in a letter from the kaymakam to the voivode of Athens, never by the Sultan, and again, the letter did not mention permission to remove the marbles.

— How much did the British Parliament pay for them?

At the time, 35.000 pounds.

— You spoke to me about stubbornness, it is a political issue after all. How many people want to return the sculptures?

If you look at the statistics in favour of return, we are talking about 60% of the British people. After the recent reunification of the Fagan fragment from Palermo, I think the percentage will be higher. Return is one thing and reunification is another.

— Can you explain it to me?

Return means coming back to Greece, to Athens. Reunification, that they will no longer be orphaned. They will be reunited with their sister parts, here at the Acropolis Museum. Gone will be the plaster casts that are exhibited here today, next to the originals; the original sculptures from the British Museum will be put in their actual place, which is even more moving for the British people and the world public. Let me say one more thing. This is not, as some people want to make it out to be, a dispute between the Acropolis Museum and the British Museum, nor between the Greek and British people, because everyone wants this reunification, and that is the essential point that all those who oppose the return must understand. The Parthenon is a symbol of global civilisation, it is not just a simple statue that has been removed which we often don’t exactly know where it comes from. The case of the Parthenon architectural sculptures is clear. They belong to the body of the temple.

— Tell me about this symbolism.

Until the Parthenon was made, temples had mythological themes depicted on their architectural sculptures; that is, in the metopes, the pediments, the friezes: depictions of centauromachy, amazonomachy, gigantomachy and so on. For the first time in the history of ideas, the Athenian republic of the 5th century BC dares to think, design and sculpt in the hard material that is marble, which can preserve beauty and symbolism through the centuries, a contemporary scene, the Panathenaic procession, with the whole spectrum of the Athenian Republic’s social structure. On the frieze are depicted young and mature, men and women, horsemen, charioteers, all the strength and the youth of the city. Also, noble lords carrying olive branches, aristocrats and mature thetes, priests, all social classes of the Athenian Republic without exception.

And lest it should be considered a hybris −for this was unprecedented in the temple of the city’s patron goddess− the frieze was placed at the highest point of the wall of the cella, at ten - twelve metres, where it could not be easily seen by the human eye, where it is impossible to distinguish their aesthetic details, the beginning of the perspective, the colors − it was only for the eyes of the gods! In this way democracy was elevated to the ideal, the divine and the eternal. Therefore, Elgin vandalized the very concept of democracy.

Today in a world full of pandemics, wars and economic crises, where the very concept of democracy is challenged, all smart leaders can do is to become protagonists, “front-runners” in the immediate reunification of the Parthenon sculptures in the Acropolis Museum, leaving aside legal, economic or other difficulties. This is what the British people and the global community are asking for and smart leaders are listening and moving in the right direction.

— You’re talking to me about the ethical part. On the legal level, what has been done so far?

Things have not progressed, nor did they progress when Amal Alamuddin came to Greece, as you remember. These issues, in my opinion, are not resolved in the courts. I also want to add here that sometimes although there are good intentions, people end up taking unlikely actions that hurt instead of help, meaning ignorance leads to overreaction; too much of a good thing…!

— What bothers you the most about the public statements being made?

Anyone can have an opinion, but it should be doing good or at least no harm. It’s one thing to have an opinion and express it in the cafeteria, it’s another thing to get the gist of things down. Every club and every university professor goes out and says whatever they want. What do you think about the fact that, from everything that has happened to date, and I’m referring to the UNESCO decision in September 2021, for the reunification of the sculptures where they belong; the ratification in Unesco’s assembly in May 2022 and the recent reunification from Palermo, instead of all these great facts, the visible part published in the press and on social media was Jonathan Williams’ sentence: “Elgin took some marbles that were on the ground around Parthenon”. It’s of course a matter of judgement on the part of the person who publishes information. They should at least have asked those who know the case and try to publish the important issues.

— Which period do you think has been the most productive regarding this claim?

To be honest, after Melina (Merkouri), all Greek governments, fortunately, tried their best. Everyone played their part, big or small. Judging by the result, the most productive period is the current one, 2021-22, with the UNESCO decision and its ratification. A committee of four persons was set up by the Ministry of Culture, consisting of the General Secretary of the Ministry of Culture, Mr. George Didaskalou, the director of the Ministry of Culture, Ms. Vaso Papageorgiou, the director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ms. Artemis Papathanasiou, and myself, who had eyes on the goal and not our personal promotion. For thirty-seven years our country has only received recommendations from UNESCO that said “you two (Greece and the UK) should figure this out yourselves”, i.e. polite wishful thinking. In September 2021 we did the presentation online from inside the Acropolis Museum, on the second floor, so that one could see behind us (behind the Committee) the archaic and classical sculptures and all the people visiting our Museum. Along with our arguments, this image seen by all the countries participating in UNESCO Assembly was also of great value. They understood that these masterpieces of classical culture, which are the basis of the world’s civilisation, must be returned to their birth place, and in the Acropolis Museum. Anyone who comes in Athens and visits the Acropolis and its Museum surrenders to the power this space emanates.

— What are the new arguments you have invoked?

First of all, we should note that at the UNESCO meeting, the British arguments regarding the new museum, pollution, fallen debris, and our written counter-arguments were presented one by one in a power point presentation. At the end, new arguments were added, namely that this rock, which has stood for hundreds of thousands of years in the Attic basin and is a reference point for all people from prehistoric times to the present day, reflects the history of thousands of years of life in Athens, culminating in the Parthenon temple, and that these marbles will not be able to “rest” unless they are under the sky and the sun that gave birth to them. It is an experience that visitors could not have anywhere else, not even in the best museum in the world. These architectural sculptures, the Parthenon, are our identity, and I am not exaggerating. The sculptures belong here, they stand taller than us; they are masterpieces of a different quality.

— Which countries have stood by you?

Mainly the countries that have suffered from colonialism, despite the fact that we were never a colony but a conquered country when the sculptures were looted. The concept and the written decision presented to the country – members of UNESCO was proposed by Zambia last September and was unanimously adopted. For the first time we left with a decision in our hands and not a recommendation, and all countries supported us. According to the decision, it is not only legal, ethical and fair to return the sculptures to Athens, but it is also an intergovernmental issue. The museums have to find a way to do it, but it is the governments that have to come together and agree.

— So this decision throws the ball in the court of the governments?

Of course. The role of the museums is clear, but now it is a government issue. When the decision came out, there was an uproar by some people in the UK who expressed their great dissatisfaction, but that was the decision. And then the British government threw the ball back in the museum’s court.

— What is their rationale?

Their position is that the British Museum is independent and decides on the sculptures and exhibits in it. But is that the case? The British Museum is indeed an independent legal entity, but how much autonomy does it have when the twenty-five members of its board of Trustees and Directors are appointed by state bodies? After all, its budget comes entirely from the Ministry of Culture and the museum is accountable to the British Parliament. Its administrative and managerial status is determined every five years by contract. It is also bound by a 1963 Act of the British Parliament under which no exhibits may be removed from the British Museum. Of course, things have changed since then. For example, works confiscated by the Nazis were returned by the British Museum, and the British state even ran a morality campaign saying that those who own similar works in other countries should return them.

— So we’re talking about the moral level. Can we talk on a legal level, would it be beneficial?

I don’t think so, as I have already explained earlier.

— Do you think the decision to return the marbles will be made on the basis of ethics?

I think it will be made on the basis of the conscience, the ethics and the general demand of the British people and the global community.

— How will this be done in 2022?

Huge changes are taking place, look at what “The Times”, “The Guardian” and “Le Monde” are saying - leaders cannot ignore the wishes of those who elect them. Britain may not be the empire it used to be in the nineteenth century, but can become a frontrunner in the moral struggle of global civilisation with a single act. Just as the law was passed in 1963 that prohibited, among other things, the return of the sculptures, today, with a similar law in the British Parliament, this can be changed so that the Parthenon marbles can be returned and reunited.

— What do you answer when people say that the museums of Europe will be emptied?

I even hear this argument from educated people. We, as a country, as far as I know, are only asking for the Parthenon marbles.

— The British say the marbles are part of the history of their museum.

Can a piece of the museum’s 200 years of history, which the museum holds without any moral basis, be compared to two and a half thousand years of a people’s history and their identity? How does one weight these things against each other? Forcible seizure is immoral at its base, the dismemberment and division of democracy itself −conceptually−, the plundering of the symbol of the global civilisation, the Parthenon. The body of the Parthenon is always asking for its missing members, and that is what the global community is demanding. Every part of it should be returned and be reunited to the rest of the body of the Parthenon.

— It is also the worst aspect of so-called philhellenism, the dismemberment, the case of Lusieri.

This particular philhellenism is the cult of appearances, not essence.

— The British claim that the Duveen Gallery will be emptied.

All Greek governments, as far as I know, have said they will replace the works, but I would suggest that they take out of their warehouses other masterpieces that are Greek, but we have not claimed them, for example the frieze of Figalia. But what our governments are saying is enough to end this tall tale.

— Let’s move on to the significance of the Fagan fragment and our relationship with Sicily.

This small piece from Palermo, joined forever, “per sempre”, in stone VI of the eastern frieze, is in fact a huge piece, a cornerstone in terms of symbolism. The definitive return and reunification of the Sicilian piece is of immense importance, since we all know that the beginning is half of everything. It is also most important that for the first time the understanding is being reached between states, without legal or other interference, on the basis of conscience, morality and justice.

— Is it related to the route of the Parthenon sculptures?

As the director of the Palermo museum, Caterina Greco, said, the Fagan fragment was found in the collection of Robert Fagan, British consul in Sicily at the very same time that the sculptures were removed from Athens by Elgin and his associates. In my speech during its reunification to the frieze in the Acropolis Museum on Saturday, June 4, 2022, I said: “Imagine if it is proven by the investigation that it is not implausible that Elgin himself gave it to Fagan during the journey of the stolen Parthenon marbles from Athens to Britain. If this is the case, then it would be the first Elgin marble to return, with all this could signify”. You understand what I mean.

— Despite the fact that it was not done through legal procedures, it is a state-to-state return, the first reunification of the Parthenon marbles.

Indeed, the definitive reunification was achieved thanks to the conscience and love of our Sicilian friends who share the same principles and values as we do with regard to cultural assets removed from monuments and the places where they belong. It is the first reunification of this monument to take place state-to-state, thus showing the path to be followed by other countries, notably the United Kingdom, contributing to the restoration of the Parthenon −the monument which is a symbol of global civilisation− and to the restoration of history and democracy.