Πριν από δέκα χρόνια (σαν σήμερα) πέθανε ο Douglas Adams. Γυμναζόταν σε ιδιωτικό γυμναστήριο εκείνη τη στιγμή - και νομίζω μας έστειλε ένα μήνυμα ακόμα και με το θάνατό του (!). Ήταν 49 ετών.

Είχε συνεργαστεί με τους Μόντι Πάιθον, είχε γράψει τέλεια βιβλία (την πανέξυπνα αστεία πενταλογία Γυρίζοντας το Γαλαξία Με Ωτοστόπ, αλλά και άλλα, με ήρωα τον αγαπημένο μου κωμικό ντετέκτιβ Dirk Gently), δήλωνε άθεος όταν οι άλλοι ντρέπονταν, νοιαζόταν για τη φύση και έγραφε για τα ζώα που απειλούνταν με εξαφάνιση, και μας αποκάλυψε πως η απάντηση στα ζητήματα ζωής και σύμπαντος ήταν ο αριθμός 42.

Επίσης ήταν πρωτοπόρος στα τεχνολογικά. Ο πρώτος Άγγλος που αγόρασε Mac, χρησιμοποιούσε προϊόντα Apple απ' το 1984 ως το θάνατό του το 2001. Στα τέλη των '90ς ετοίμαζε ένα πρωτοποριακό σάιτ που θα ήταν το αντίστοιχο Hitchhikers' Guide to Galaxy για τον πλανήτη μας.

Ήταν, με δυο λόγια, ένας υπέροχος άνθρωπος. Απ' αυτούς που στεναχωριέμαι που πέθαναν νέοι για τον επιπλέον λόγο πως είμαι σίγουρος πως στη συνέχεια θα έγραφαν ακόμα καλύτερα βιβλία, θα έφτιαχναν ακόμα καλύτερη τέχνη, μ' έναν ζεστό ανθρωπισμό.

Με αφορμή τα δέκα χρόνια απ' το θάνατο του Douglas Adams αναδημοσιεύω (στο πρωτότυπο) ένα πανέξυπνο άρθρο που είχε γράψει για το ίντερνετ το 1999, τότε που υπήρχαν ακόμα άνθρωποι που πίστευαν πως το ίντερνετ ήταν μια μόδα που σε 2-3 χρόνια θα περνούσε...

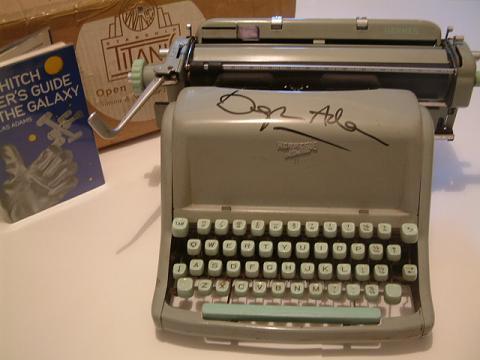

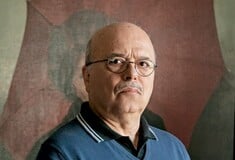

[H γραφομηχανή που χρησιμοποίησε για το Γυρίστε το Γαλαξία με Ωτοστόπ. Πριν τους Mac και το αγαπημένο του ίντερνετ.]

How to Stop Worrying and Learn to Love the Internet

This piece first appeared in the News Review section of The Sunday Times on August 29th 1999.

A couple of years or so ago I was a guest on Start The Week, and I was authoritatively informed by a very distinguished journalist that the whole Internet thing was just a silly fad like ham radio in the fifties, and that if I thought any different I was really a bit naοve. It is a very British trait – natural, perhaps, for a country which has lost an empire and found Mr Blobby – to be so suspicious of change.

But the change is real. I don’t think anybody would argue now that the Internet isn’t becoming a major factor in our lives. However, it’s very new to us. Newsreaders still feel it is worth a special and rather worrying mention if, for instance, a crime was planned by people ‘over the Internet.’ They don’t bother to mention when criminals use the telephone or the M4, or discuss their dastardly plans ‘over a cup of tea,’ though each of these was new and controversial in their day.

Then there’s the peculiar way in which certain BBC presenters and journalists pronounce internet addresses. It goes ‘www DOT … bbc DOT… co DOT… ukSLASH… today SLASH…’ etc., and carries the implication that they have no idea what any of this new-fangled stuff is about, but that you lot out there will probably know what it means.

I suppose earlier generations had to sit through all this huffing and puffing with the invention of television, the phone, cinema, radio, the car, the bicycle, printing, the wheel and so on, but you would think we would learn the way these things work, which is this:

1) everything that’s already in the world when you’re born is just normal;

2) anything that gets invented between then and before you turn thirty is incredibly exciting and creative and with any luck you can make a career out of it;

3) anything that gets invented after you’re thirty is against the natural order of things and the beginning of the end of civilisation as we know it until it’s been around for about ten years when it gradually turns out to be alright really.

Apply this list to movies, rock music, word processors and mobile phones to work out how old you are.

This subjective view plays odd tricks on us, of course. For instance, ‘interactivity’ is one of those neologisms that Mr Humphrys likes to dangle between a pair of verbal tweezers, but the reason we suddenly need such a word is that during this century we have for the first time been dominated by non-interactive forms of entertainment: cinema, radio, recorded music and television. Before they came along allentertainment was interactive: theatre, music, sport – the performers and audience were there together, and even a respectfully silent audience exerted a powerful shaping presence on the unfolding of whatever drama they were there for. We didn’t need a special word for interactivity in the same way that we don’t (yet) need a special word for people with only one head.

Because the Internet is so new we still don’t really understand what it is. We mistake it for a type of publishing or broadcasting, because that’s what we’re used to. So people complain that there’s a lot of rubbish online, or that it’s dominated by Americans, or that you can’t necessarily trust what you read on the web. Imagine trying to apply any of those criticisms to what you hear on the telephone. Of course you can’t ‘trust’ what people tell you on the web anymore than you can ‘trust’ what people tell you on megaphones, postcards or in restaurants. Working out the social politics of who you can trust and why is, quite literally, what a very large part of our brain has evolved to do. What should concern us is not that we can’t take what we read on the internet on trust – of course you can’t, it’s just people talking – but that we ever got into the dangerous habit of believing what we read in the newspapers or saw on the TV – a mistake that no one who has met an actual journalist would ever make.

Of course, there’s a great deal wrong with the Internet. But the cost of powerful computers, which used to be around the level of jet aircraft, is now down amongst the colour television sets and still dropping like a stone. Modems these days are mostly built-in, and standalone models have become such cheap commodities that companies, like Hayes.. Internet software from Microsoft or Netscape is famously free. Phone charges in the UK are still high but dropping. In the US local calls are free. In other words the cost of connection is rapidly approaching zero, and for a very simple reason: the value of the web increases with every single additional person who joins it. It’s in everybody’s interest for costs to keep dropping closer and closer to nothing until every last person on the planet is connected.

But the biggest problem is that we are still the first generation of users, and for all that we may have invented the net, we still don’t really get it.

However, the first generation of children born to the community takes these fractured lumps of language and transforms them into something new, with a rich and organic grammar and vocabulary...

We are natural villagers. For most of mankind’s history we have lived in very small communities in which we knew everybody and everybody knew us. But gradually there grew to be far too many of us, and our communities became too large and disparate for us to be able to feel a part of them, and our technologies were unequal to the task of drawing us together. But that is changing.

Interactivity. Many-to-many communications. Pervasive networking. These are cumbersome new terms for elements in our lives so fundamental that, before we lost them, we didn’t even know to have names for them...

σχόλια