During a period of six months prior to the German invasion of Greece a group of workers and archaeologists was digging the floors of the National Archeological Museum to bury Athens’s most valuable treasures: its Kouroi and Lekythoi.

______

On Sunday 27th April 1941 the German troops occupied Athens. Early the next morning, when the German officers hurried up the marble steps of the National Archaeological Museum, they were surprised to discover that they were taking over an empty building. They couldn’t find a trace of the thousands of valuable exhibits that were housed in the country’s largest museum for the past sixty years of its existence. Instead of statues they saw before them the few frozen and expressionless archaeologists and guards who were on duty at the time. To the officers’ persistent questions, the latter answered enigmatically that antiquities are always where everybody knows they are: under the ground. And it was true. The antiquities had in fact returned underground – to the only ark in the world where they would be safe.

The Greek governments were aware of the fragile European order well before the war started. Since 1937 the Metaxas(2) government had started corresponding with the Archeological Department of the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs to work out a common plan of how to protect antiquities from potential air raids and street fights. To the state’s demand that they put together catalogues and classify the antiquities according to their importance, the archaeologists of the department insisted that there was no way to make such a choice and that all antiquities (exhibited or stored) would have to be saved in the event of war. As a matter of fact, there were internal recommendations in 1937 to transport the antiquities to new places of storage, safe from fire or bombing, at “archaeological towns” proclaimed sacred and inviolable by international agreements, rather than spending large sums for the construction of shelters for some of them. The area of the Acropolis was to be one of them. Yet, reality dissolved any hopes and the few doubts about the impending disaster.

Preparations against the danger of destruction got more intensive with time. With the declaration of war in October 1940, the Department of Archaeology reacted instantly. With a letter sent out on 11th November 1940 to all local sections, it issued technical instructions “for the protection of antiquities in the various museums from air-raid danger”. These included two ways of protecting bulky and non-transportable exhibits: The first one was “to cover the statue with sandbags after protecting it with wooden scaffolding like the sample” and the second one, which was deemed more effective, was to bury the statues in the floor of the hall or the courtyard of the museum or in protected courtyards and basements of public institutions. The burying method was then described in full detail. The statues were to be placed horizontally (like dead bodies in a grave) at the bottom of the ditch which was to be clad in reinforced cement, then covered by inert materials, after which the ditch was to be sealed with a slab. As for copper and clay items, they were to be stored in crates covered with waxed or tarred paper in order to resist humidity.

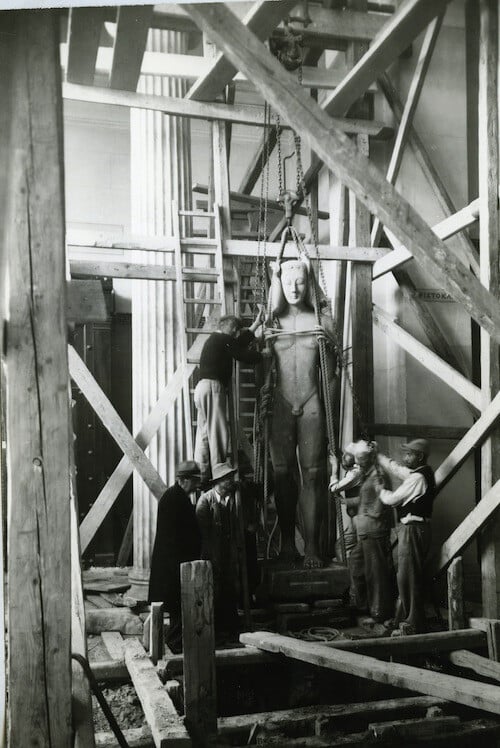

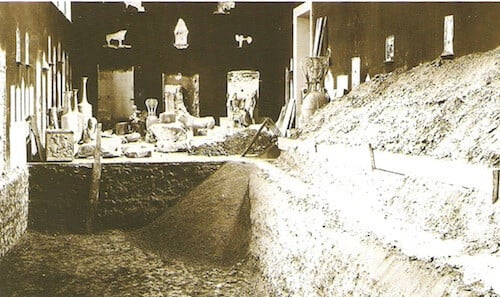

At the National Archaeological Museum the alarm sounded off! By a ministerial decree a committee in charge of hiding and securing the museum’s exhibits was formed, headed by 3 Supreme Court Judges (AEROPAGITES) and including the secretary of the Archaeological Society George Oikonomou, the temporary director of the museum Anastasios Orlandos, and professor Spyridon Marinatos, as well as curators Giannis Miliadis, Semni Karouzou, Ioanna Konstandinou and civil engineers and architects from the ministry. Volunteers subsequently joined the team, such as the director of the Austrian Archaeological Institute Otto Walter, the British archaeologist Allan Wace, and the academician Spyros Iakovidis who was a freshman archaeology student at the time. “Really early in the morning, even before the moon had set, the people who had undertaken this job would gather at the museum and they would leave for home really late at night”. Semni Karouzou writes. The storing of the statues would take place according to the size and importance of each one. The bulkiest among them would be lined up standing in deep ditches that had been dug in the floors of the North halls of the museum, whose foundations happened to lay on softer underground. Improvised wooden cranes were used in order to lower the statues into the ditches, and were handled incessantly by the museum’s technicians. The ditches that were reminiscent of mass graves enclosed a dazed multitude of forms, such as the one illustrated in the most valuable of photographs from the museum’s archive (images 5 &6). Amongst the forms of the statues standing awkwardly in their new grave we find one of the anonymous protagonists of this epic of concealment: a technician looking absent-mindedly at the camera lens. As he ponders the uncertain fate of the times, he completely blends in with the surrounding crowd. ‘’If there was no damage done to the marbles despite all the displacements, it is mainly due to the fact that the manager of the workers team at the time was, and remained until the first years after the war, the old experienced and devoted sculptor of the Greek museums, Andreas Panayotakis”, Semni Karouzou recounts.

“In October 1940, when Italy declared war, I had just entered the first year of University” remembers Spyros Iakovides, member of the Athens Academy, in an interview. “The hiding effort had already started and I offered to volunteer. They sent me to one of the storage rooms where there were huge crates. My job was to wrap the Tanagra figurines(3) in old newspapers and then place them carefully in the crates. After that, a special committee took over. We all worked against the clock, in fear of the German invasion, and of course, with utmost care. The Tanagra figurines were easy to wrap. But the vases were very fragile. The work was done in the museum’s basements. The statues were placed like people in a demonstration. Then sand was poured on top, separating the statues from each other yet covering them completely. Finally, a slab of concrete was poured on top. The windows in these basements were sealed with sandbags. This way, nothing could happen during an air raid”. The wooden crates with the clay vases, the figurines, as well as the copper items, were placed in the semi-underground extension of the museum, which had just been completed, towards Bouboulinas street. Subsequently, the rooms were filled up to the ceiling with dry sand in order to resist ruptures to the concrete ceiling in the event of bombing. One memento of this boxing-in endeavour was captured in a photo, the only one showing the museum artisans in a moment of rest. They are looking into the lens without expression – people whose fate during the hard years of the German occupation of Athens is unknown. Semni Karouzou has preserved the name of one of them: “During the whole work of the uprooting and boxing-in of the antiquities of the Collection of Vases and Small Artefacts, a leading role was played by a head artisan, the late Giorgios Kontogiorgis – an architect and one of the artisans who offered so much towards the fame and safety of the antiquities. Along with the antiquities, the boxing-in included the valuable museum inventory catalogues, i.e. the books documenting and registering its treasures. These crates were handed over to the general treasurer of the Bank of Greece on 29th November 1940 (4). On 17th April 1941 the wooden crates filled with the golden objects and famous treasures from Mycenae were delivered to the headquarters of said bank. It was the final act of a six-month operation that had succeeded in saving the immeasurable treasures of the largest museum in the country. “The view of the museum in April 1941, stripped from all its content, was an image of abandonment. Naked walls, dug-up floors in many halls, empty showcases”. This was the view seen by German officers on the morning of Monday 28th April: the first day of the German occupation of Athens.

In the difficult years that followed, the museum did not remain deserted. The State Orchestra was housed in the large Mycenaean Room. The Central Post Office occupied a large area of the west wing, to the right of the entrance. The Ministry of Welfare provided its services via rooms on the first floor, towards Bouboulinas street, while a special Health Service was installed in a room of the old building, off Tositsa street. “Unfortunate women, outcasts of society, were obliged to pay a visit there”, Semni Karouzou wrote. The offices of the museum staff were crammed into a small corner of the new building, together with its now useless equipment, its empty showcases, certain paintings from the National Gallery, and the General State Archives. In one of the basements of the new wing, communal meals for the guards and museum staff were prepared. The thick smoke stains on certain parts of the ceiling can still be seen today. Despite the loss of its function as a museum, the building remained undamaged until the end of the Occupation. Until “the nightmare riots of December 1944″ (between troops of the left resistance and the combined British and governmental forces) that is, when “airplane strikes” totally burnt down a part of the wooden roof, and a section of the first floor was transformed into prisons for the detainees. Some of the bullet-riddled walls have been preserved to this day, forming the backdrop of the museum staff offices today. And despite the long and labourious restoration of the building and its exhibits in the post war years, the hidden surprises that have trickled to the surface since then have been many.

Even the second, rigorous renovation that was recently completed unearthed more of the Museum’s well-buried secrets. Is this the last of them? Living and working among these walls, one knows that statements concerning chronological certainty are not admissible.

_________________________________

Translated from Greek by Diana Issidorides, Margarita Ovadia and Ares Kalandides

The article was first published in Greek in the Lifo magazine. (http://www.lifo.gr/mag/features/3704)

It appears simultaneously at http://blog.inpolis.com and http://theplayfulmind.wordpress.com

Link to the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Notes

(1) Kostas Paschalidis is an archaeologist and works as curator of antiquities at the Prehistoric Collection of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

(2) Ioannis Metaxas was dictator in Greece between 1936 and 1941.

(3) The Tanagra figurines were a mold-cast type of Greek terracotta figurines produced from the later fourth century BCE, primarily in the Boeotian town of Tanagra.

(4) Italy declared war to Greece on 28th October 1940.

References (in Greek)

Christopoulou, Α., “National Archaelogical Museum and Modern Greece. Parallel stories”, “Archaologia kai Technes” 113 (December 2009), 5-10.

Vernardou, Ε., “A hiding different from all others. Operation ‘Hidden Treasures’”, Available at www.psaxtiria.net/forum/archive/index.php/t-2897.html

Kaltsas, Ν., “The National Archaeological Museum”, Athens 2007, 20. Available at www.latsis-foundation.org/megazine/publish/ebook.php?book=31&preloader=1

Karouzou, S., “Short History of the National Museum”, in Karouzos, S. National Archaeological Museum, Collection of Sculptures, Descriptive catalogue, Athens 1967, ια’-κ’.

Karouzou, S, “The National Museum after 1941”, To Mouseion 1 (2000), 5-14. (This is the old publication by S. Karouzou which was included in the proceedings of the 1st Conderence of the Associations of Greek Archaeologists, Athens 30th March-3rd April 1967, Athens, 52-63.)

Nikolakea, Ν., “The protection of antiquities during World War II” Tsitopoulou, M. (ed), “…I reported in writing”. Treasures of the Historical Archive of the Archaeological Service, Athens 2008, 57-59.

Paschalidis, K. “The founding, history and adventures of the National Archaeological Museum, 130 years of service in one lecture. Available at:www.blod.gr/lectures/Pages/viewlecture.aspx?LectureID=737#.UTcIWTbYhgU.facebook

Petrakos, V. X. “The antiquities in Greece during the war 1940-1944», O Mentor 31 (1994), 73-185.

Salta, M. “National Archaeological Museum” in Garoufalis, D.N. & Konstantinidi-Sybridi, E. (eds.) Archaeology in Greece. The greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century and the treasures of the Greek museums, Athens 2002, 116-119 (Series: History of Civilisations No2 by the magazine “Corpus”).

Flessa, V. “At the edge”, interview with the acedemician S. Iakovidis at the New Greek Television (26/10/2012, 23:00 hrs). available at: www.ert.gr/webtv/net/item/8196-Spyros-Iakwbidhs-Archaiologos-Akadhmaikos-26-10-2012#.UUo0TDfQ709

σχόλια