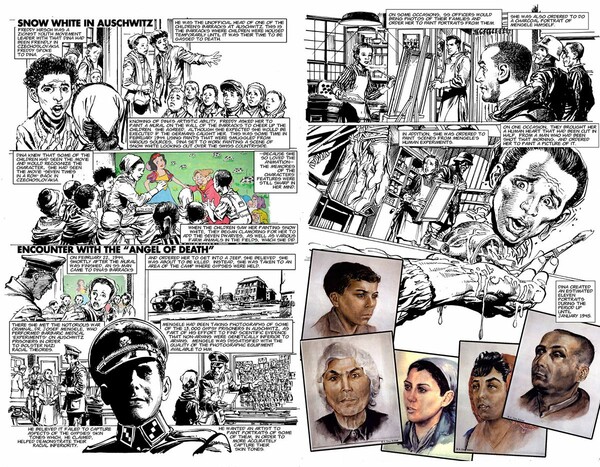

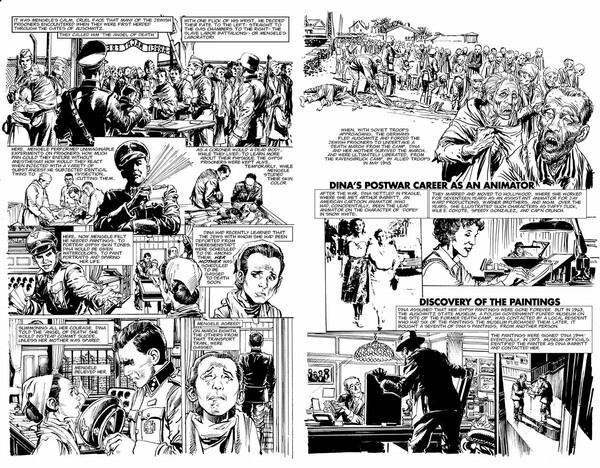

Λευκό χιόνι πάνω στο Auschwitz (2012), graphic novel των Neal Adams, Joe Kubert και Rafael Medoff στη μνήμη της Dina Babbitt. Βλ. As Seen Through These Eyes.

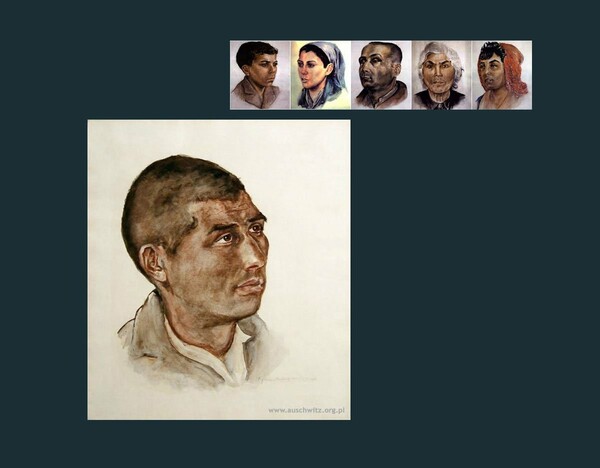

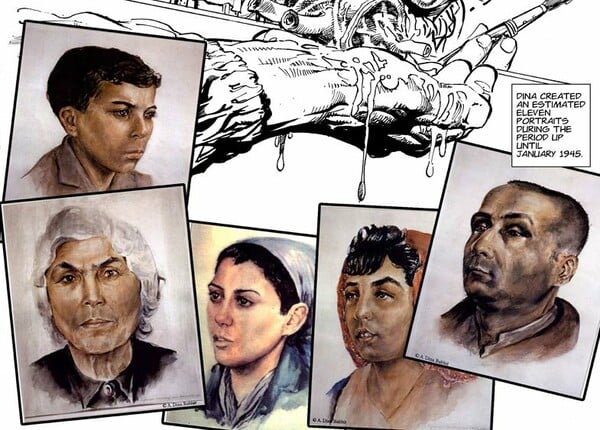

Ακολουθώντας με τη δική της θέληση τη μητέρα της στο στρατόπεδο του Auschwitz, η Dina Babbitt προθυμοποιήθηκε να ζωγραφίζει εκεί τις παράγκες των παιδιών με σχέδια που θυμόταν από τη Χιονάτη, την οποία είχε δει επτά φορές στον κινηματογράφο. Τα σχεδιά της τράβηξαν την προσοχή ενός αξιωματικού των SS που έκρινε σκόπιμο να την παρουσιάσει στον περιβόητο ναζιστή ιατρό Josef Mengele. Εκείνος της ζήτησε να του ζωγραφίσει τα πορτρέτα των Τσιγγάνων που κρατούσε για τα "πειραματά" του πριν τους στείλει στο θάνατο, με την υπόσχεση ότι τόσο η Dina Babbitt όσο και η μητέρα της θα ήταν ασφαλείς. Όπως και έγινε. Από τους 3.800 Εβραίους της Τσεχίας που βρίσκονταν στο Auschwitz, μόνο 22 επέζησαν από τους θαλάμους αερίων. Η Dina Babbitt και η μητέρα της είχαν την τύχη να συγκαταλέγονται αναμέσα σ' αυτούς. Το 1963, το Εθνικό Μουσείο Auschwitz-Birkenau απέκτησε έξι από τα πορτρέτα Τσιγγάνων της Dina Babbitt και ζήτησε από τη ζωγράφο, όταν το 1973 εξασφάλισε κι ένα έβδομο, να πιστοποιήσει την αυθεντικοτητά τους. Η Dina Babbitt επισκέφτηκε το Μουσείο, αναγνώρισε τα έργα της και... τα ζήτησε πίσω. 'Εκτοτε ξεκίνησε μία μεγάλη διαμάχη που κράτησε 30 ολόκληρα χρόνια χωρίς τελικά το Μουσείο να ενδώσει στο αιτημά της.

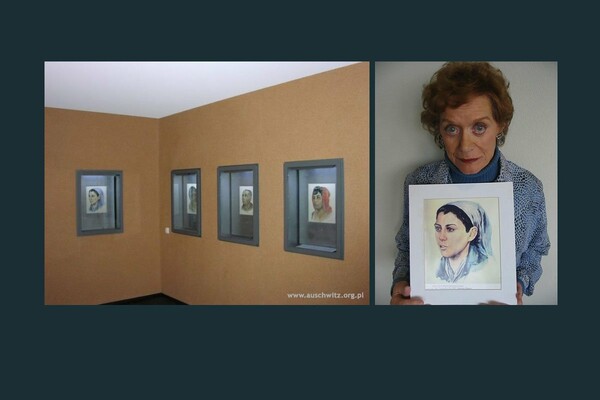

Αριστ., η αίθουσα του Μουσείο Auschwitz-Birkenau με τα πορτρέτα της Dina Babbitt. Βλ. ferrin.livejournal.com. Δεξ., η ζωγράφος με ένα αντίγραφο από τα σχεδιά της. Βλ. As Seen Through These Eyes.

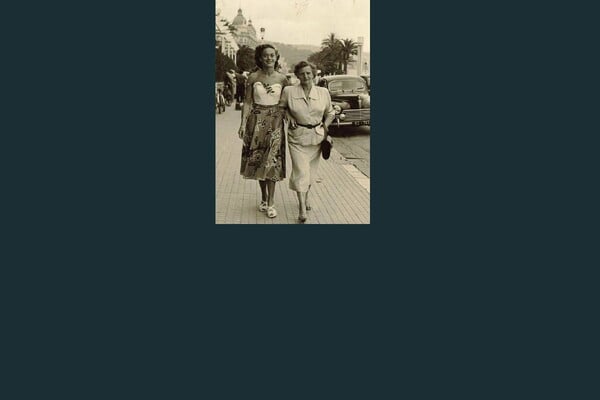

Η Dina Babbitt με τη μητέρα της στη Νίκαια της Γαλλίας μετά τον πόλεμο. Το 1949, παντρευτήκε τον δημιουργό κινουμένων σχεδίων Art Babbitt (ο οποίος συμπτωματικά είχε δουλέψει για τη Χιονάτη του Walt Disney) και μετακόμισε μαζί του στο Hollywood. Βλ. New York Times.

'Εξι από τα πορτρέτα των Τσιγγάνων. Βλ. artfordina.wordpress.com και New York Times.

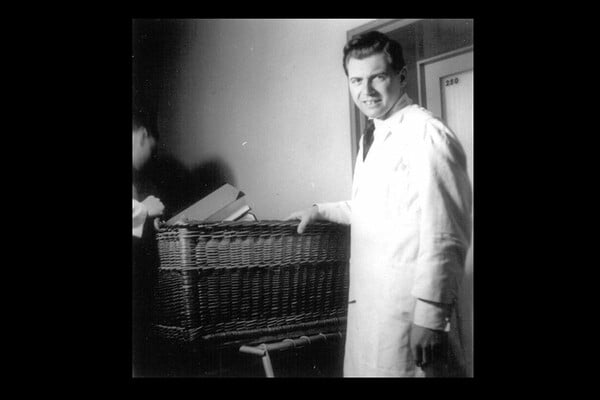

Ο Josef Mengele σε μία φωτογραφία του 1935. Κρυμμένος μετά τον πόλεμο σε διάφορες χώρες της Λατινικής Αμερικής, έζησε τα τελευταία χρόνια της ζωής του απομονωμένος σε ένα δύαρι στο São Paulo, παραμένοντας ατιμώρητος για τα εκατοντάδες θύματα που προκάλεσε. Βλ. jornalgrandebahia.com.

Λευκό χιόνι πάνω στο Auschwitz (2012). Βλ. babbittblogbabbittblog.com και

As Seen Through These Eyes.

Λευκό χιόνι πάνω στο Auschwitz (2012). Βλ. babbittblogbabbittblog.com και

As Seen Through These Eyes.

Βλ. peliculasdelholocaustojudio.blogspot.com.

They Spoke Out: The Dina Babbitt Story.

Η απάντηση του Μουσείου του Auschwitz στο αίτημα της Dina Babbitt (2-10-2006):

Dinah Gottliebova, born in Brno, as a Jewish Czech was deported to Auschwitz Concentration Camp with the transport of Jews from Theresienstadt. Together with her mother she was placed in one of the sections of the Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp, the so-called Terezin Family Camp. Prior to the war she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts and her skills of painting mastered there most probably saved her life. After her painting skills had been discovered in the camp (amongst others she painted on the walls of one of the camp barracks several scenes from Disney movies), Dr. Mengele - at that time the Chief Doctor of the so-called "Gypsy Family Camp," assigned her the task of painting the water-colors.

They showed Gypsies from various European countries. These portraits were supposed to be to Mengele a help and documentation of the criminal experiments and research on the Nazis’ theory of race, conducted by himself in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Dinah Gottliebova and her mother managed to survive.

After nearly thirty years since the end of the war she got to know about the fact that some of the water-colors she painted had not been destroyed. Just like in many similar situations these works survived by chance. In January 1945, three days after the liberation of Auschwitz Concentration Camp, one of inhabitants of the town Oświęcim, a teenager, came to the camp to take with him a bereaved Jewish girl from Hungarian transports, who got adopted by the boy’s parents. One of the survivors, touched by the boy’s behavior gave him as a sign of appreciation a roll of pictures.

They were six water-colors signed „Dinah 1944." The foster family loved and cared about the girl. Ewa graduated from a secondary school and then the Medical Academy in Cracow. Afterwards she started to work as a dentist.

In 1963 the Museum bought from Ewa six water-colors, the seventh was purchased in 1977 from another former prisoner. In the official record of the Museum Artifacts Purchase Committee from December 1963 it reads among others that: „The Committee members bought on purpose all paintings for the Museum collections as the portraits of Gypsies are closely connected with the camp history (Gypsy camp). (...) It has been determined that the portraits of Gypsies were probably painted in the concentration camp at the time of its existence, in all likelihood by a prisoner...."

Six years later the head (at that time) of the Collections Department of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum browsing through a book published by Otto Kraus and Erich Kulka entitled „Tovarna na Smrt" noticed a picture. It was signed the same way as the water-colours owned by the Museum. This way it was possible to determine the full name of the author: Dinah Gottliebova. At that time she was already living in the United States.

The moment the Museum found Mrs. Gottliebova’s address it made contact with her, informing on the existence of the works created by her in the camp. In January 1973, using the opportunity of being in Paris, Mrs. Gottliebova came to Poland and gave the Museum a testimony concerning her stay in the camp and the Gypsy portraits painted there. At the conclusion she said: "I am happy having survived the camp and I am happy to be alive. I would be grateful if I could obtain photographs of the Gypsy portraits, originals of which are in possession of the Museum and which I painted in the camp."

It was the first and the only Mrs. Gottliebova’s contact with the Museum until the second half of the nineties. In December 1973 a written copy of the recorded testimony was sent to the author and - according to her wish - two sets of photographs of the Gypsy portraits. Because the letter had not been answered and the package had not been returned either, during the next few years the Museum tried to get in touch with Mrs. Gottliebova by sending other letters. Also those letters remained unanswered and not returned by post. The Museum concluded then that Mrs. Gottliebova, in regard to tragic memories connected with the camp, did not want to stay in touch with the institution and recall the tragic past.

However the truth appeared to be different. For some time Ms. Gottliebova has been claiming back pictures painted by her, currently held at the Museum. In the light of law, the rightful owner of the seven Gypsy portraits is the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. In what regards the author property rights, they belong to Ms. Gottliebova. The Museum being the rightful owner, but without the property rights, is allowed to use them within the limits of permissible public use of protected artifacts, determined in regulation regarding author rights and relative rights.

The Museum fully understands the emotional attitude of Ms. Gottliebova to the works made in the past in conditions which undoubtedly influenced her life. However, realizing its statutory tasks the Museum is profoundly convinced that the water-colors should remain in Oświęcim. From the moment of its establishment, this institution has been – with great effort – collecting and preserving most various post-camp remains, doing everything for them to survive and certify about the crimes committed by the Nazis in the place they are most closely connected with. Both death certificates, prisoner cards, etc., produced in large number by scrupulous Nazi camp bureaucracy and works of art created in the camp, either made by prisoners on orders of the SS or illegally, are a unique document and piece of evidence, having the biggest meaning, significance and impact in the place of their creation.

Throughout the period of the camp existence hundreds of thousands of documents had been created. The majority of them is the creation of Nazi bureaucratic machine keeping registers of prisoners, and companies co-operating with the SS during construction works on both the camp and gas chambers.

Prisoners were forced to work in particular offices and camp departments and therefore a part of the documentation is signed. These are works of art as well as for instance technical plans of buildings or expansion of the camp, signed by prisoners who made them on the SS orders. These are also photographic portraits made by still living former prisoners employed in "Lagererkennungsdienst (camp identification service)." Part of the preserved suitcases, brought by the Jews who came to meet their death, is marked with the names and other data of their owners.

All these objects are closely connected with the place of extermination of Jews, Poles, Gypsies, Russians and others. They are integral part of former Auschwitz Concentration Camp, which twenty years ago was included in the UNESCO list of the World Heritage. Every lost piece of this tragic world' s heritage is a tremendous loss to all the people who come here to commemorate the victims and to conduct historical research.

A theoretical question might be asked: what will happen if other former prisoners or their heirs start coming here and claiming back – which would be rightful in their opinion – works of art, pictures, suitcases, plans drawn in the camp or other objects belonging to them or to their relatives? An example would be the gate „Arbeit macht frei" which was made in the camp’s forge by the master of artistic smithing, then an Auschwitz prisoner Jan Liwacz.

How should behave the inhabitants of Brzezinka who even nowadays are able to recognize in the camp barracks doors and windows of their pre-war houses or posts of their fences with inscribed initials and dates of their creation? The Museum fully understands individual rights but it was established to serve all – as a place of memory and the only of a kind research center – and therefore, fully respecting the rights of people who created part of documents being held here, we believe that every piece lost from the collections of this memorial will be an irreparable loss.

Seven water-colors painted by Ms. Gottliebova is only a small fraction of the rich collections of the Museum. There are a few thousand artifacts – works of art – in the Museum’s Collections Department. About two thousand of them were made in the camp by the prisoners. They are both works made on the orders of the SS (the case of Dinah Gottliebova) and created at the real risk of one’s life (e.g. illegal works of art representing drastic scenes from the camp life).

Hundreds of thousands of other documents can be seen in the archives. The Museum is not, as a rule, an art gallery. Still, its statutory obligation is to gather all evidence of crime as well as all items related with the history of Auschwitz, including artwork. In this context the portraits of the Roma people are, regardless of any interpretation, a document. The Museum has also a duty to render all documents accessible to persons researching the history of the camp. And it does, making the documents available in its every day work. It goes both for the archives as the collections.

Original works of Dinah Gottliebova are on displayin the first permanent exhibition of this kind in Poland and the second in Europe on the Destruction of the Roma, which opened in 2001 at the Museum. Apart from that one can see, for dozens of years now, copies of two portraits by Ms Gottliebova, placed in the section of the exhibition dedicated to experiments on the Roma people, carried out by dr. Mengele. Her works were also exhibited in Poland and abroad in temporary exhibitions, including Israel. The statements that her artwork is not available to public view and therefore this unique and important body of work is essentially lost to history are therefore simply not true.

The fact of the inclusion of the Museum along with its post-camp documentation, artifacts and other remains in the List of the World's Heritage by UNESCO confirms our conviction that objects and documents found in the area of the liberated camp should remain in the Museum for ever and should be protected there.

It should be also stressed that our institution is not just a "regular" museum. The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum is unique of its kind. Every square yard of it is covered with blood of the victims of the Nazis: Jews, Poles, Gypsies, Russians and other people murdered here. The main objective of this site is to make it available to hundreds of thousands of pilgrims as well as researchers, and to document as widely as possible the crimes committed here.

The latter activity obliges us morally to preserve all evidence dating back to the wartime and related with the Auschwitz concentration and death camp and to prevent this evidence from being dispersed in any way. Once again we want to stress: every single loss of even the smallest part of the documentation will be an irreparable loss and a shadow on the memory of Auschwitz Concentration Camp victims. The water-colors are scarce surviving documents on the Holocaust committed on the Roma people. Both those Roma people who survived the mass murder and the representatives of European Roma organizations share our viewpoint that the portraits should remain in Oświęcim.

Everything that remained from Auschwitz Concentration Camp belongs to all people and is the evidence of crimes committed here. It is also a warning for the future generations. Neither documents nor proofs of Nazi criminal achievements based on the theory of destruction and extermination should and can be removed from here or placed somewhere else. Only here, in Oświęcim, they do serve the science, history and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims visiting this place every year.

σχόλια