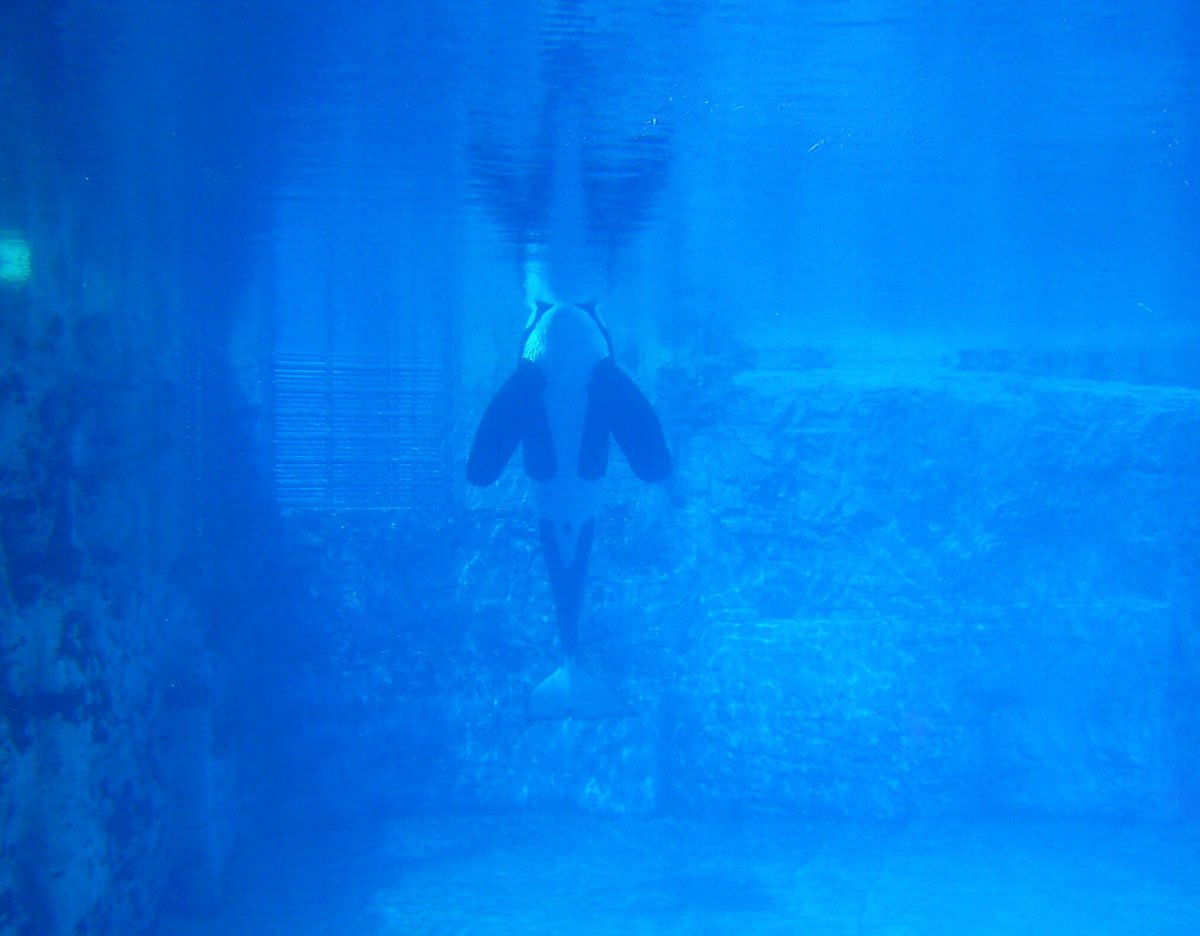

Η Keiko στη δεξαμενή της στο Newport (Oregon) τον Δεκέμβρη του 1998, λίγο πριν αναχωρήσει για τα νησιά Westman στην Ισλανδία, όπου μια ομάδα επιστημόνων θα τη βοηθήσει να επανενταχθεί στο φυσικό της περιβάλλον.

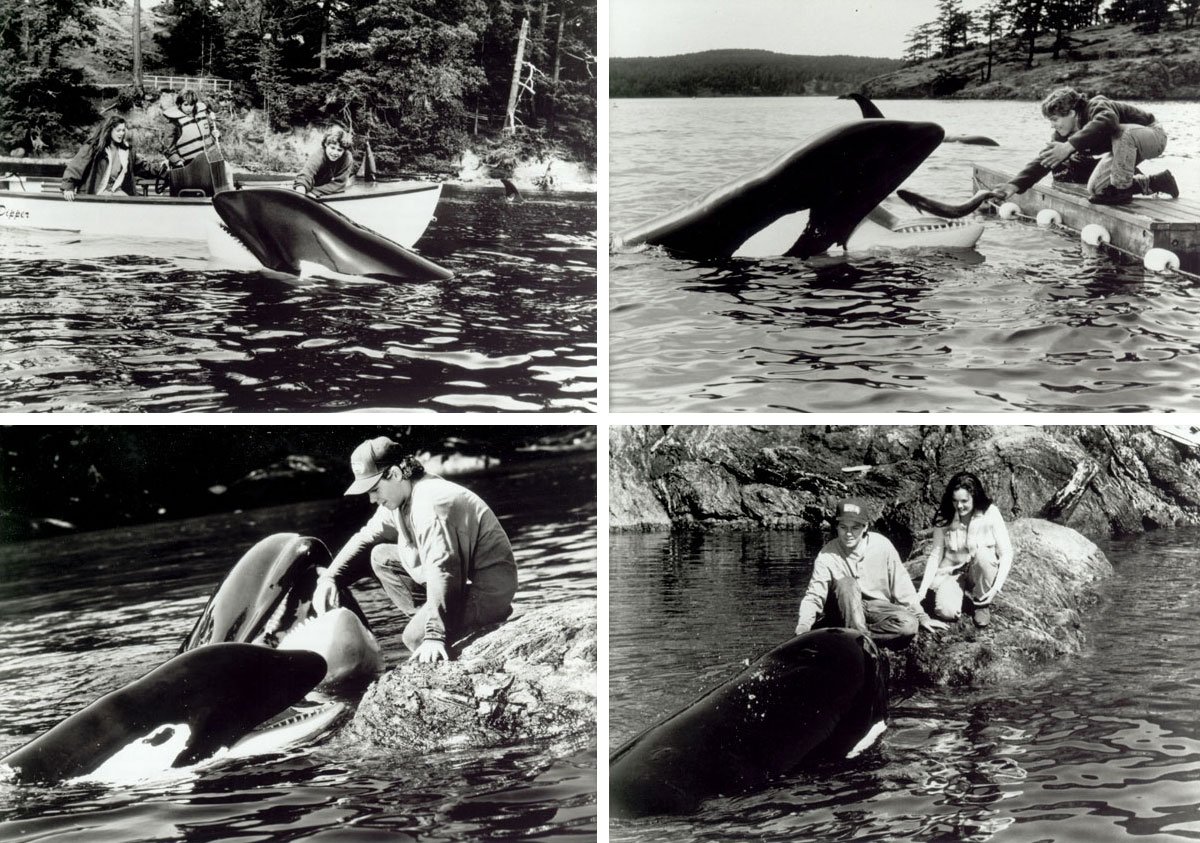

Free Willy 3 The Rescue (1997).

Free Willy 3 The Rescue (1997).

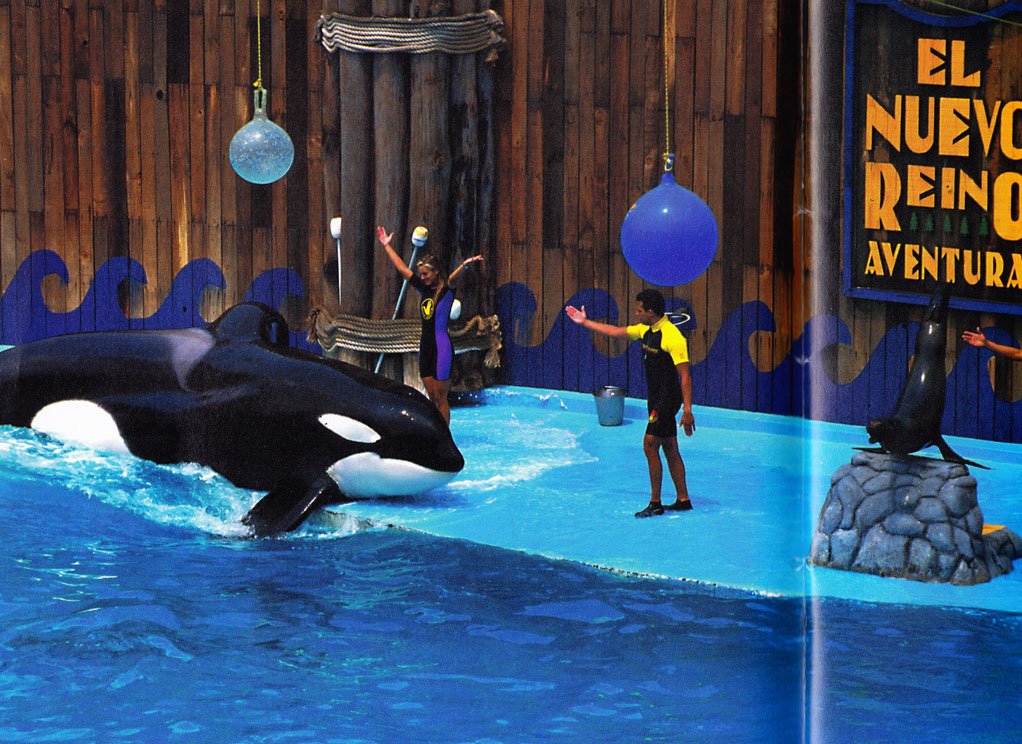

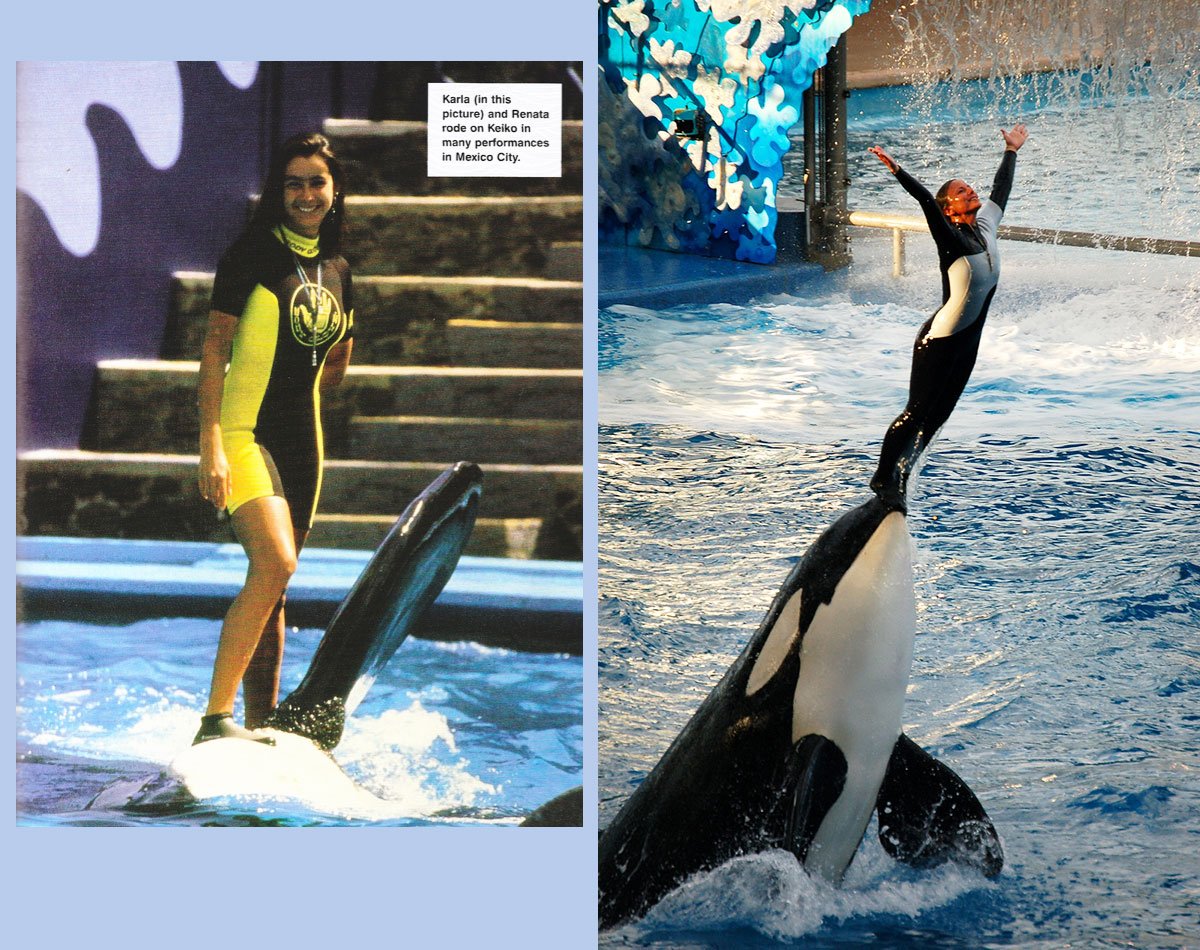

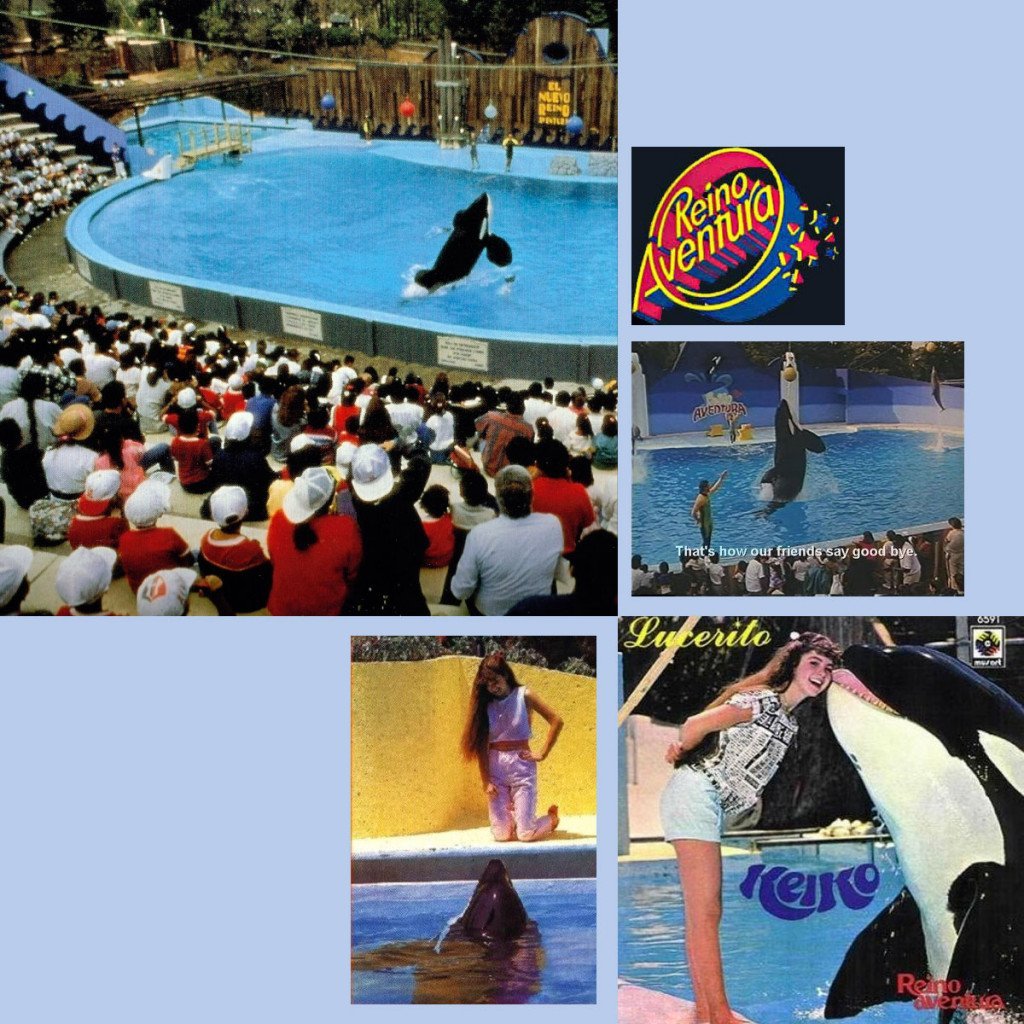

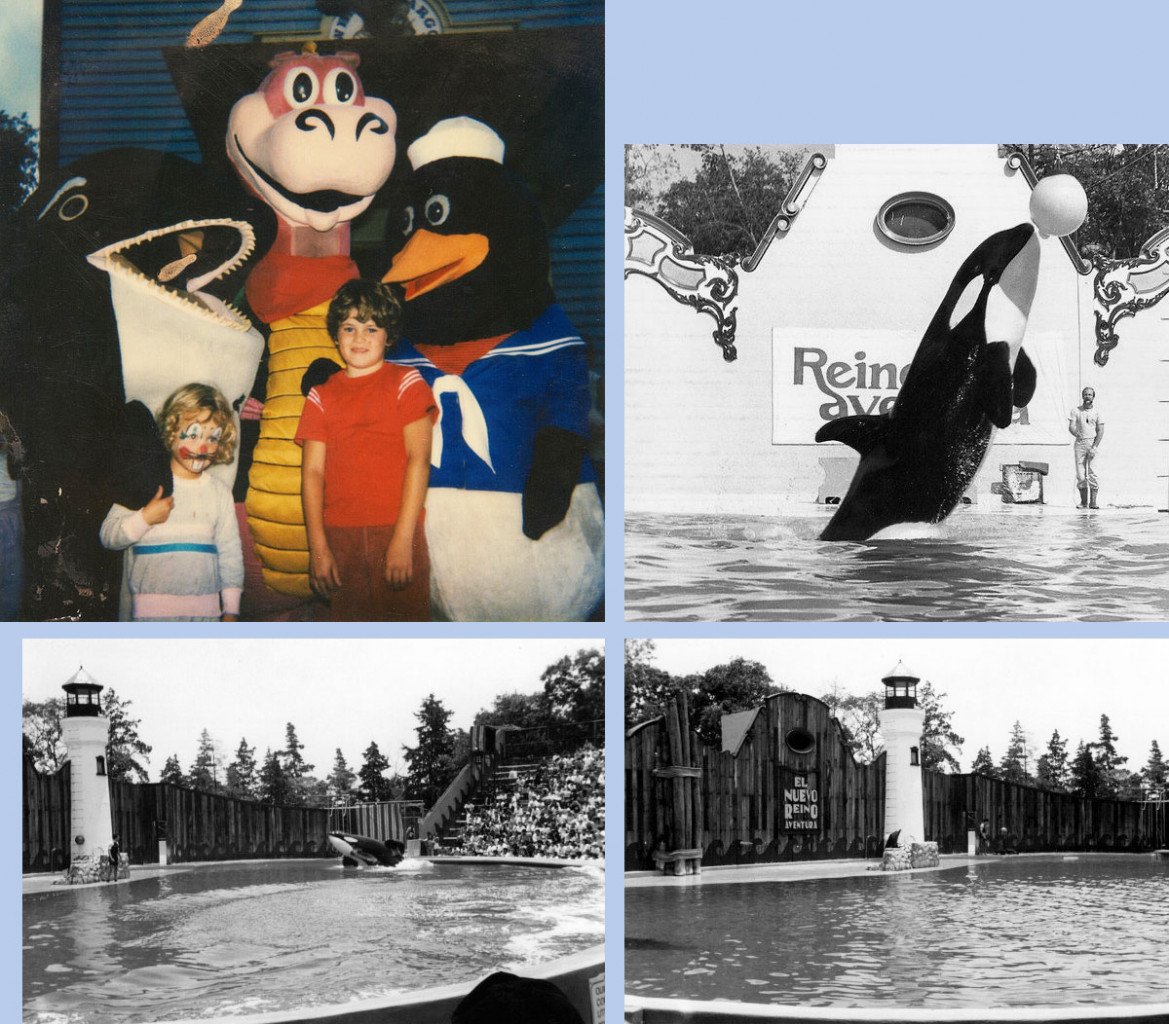

Μετά την εκπαιδευσή της στον Καναδά το 1982, η Keiko αγοράστηκε το 1985 από το θαλάσσιο πάρκο Reino Aventura του Mexico City. Το συγκεκριμένο πάρκο έχει επικριθεί ως εντελώς ακατάλληλο από φιλοζωικές οργανώσεις. Βλ. Shamufan88.

Δεξιά, η όρκα Shamu στο Seaworld της Φλόριντας που επίσης επιστρατεύτηκε για τις ανάγκες της ταινίας Ελευθερώστε τον Γουίλι.

Πάρκο Reino Aventura.

Πάρκο Reino Aventura. Η πολαρόιντ είναι από τον AndNorth, οι ασπρόμαυρες από το Mexico enfotos.

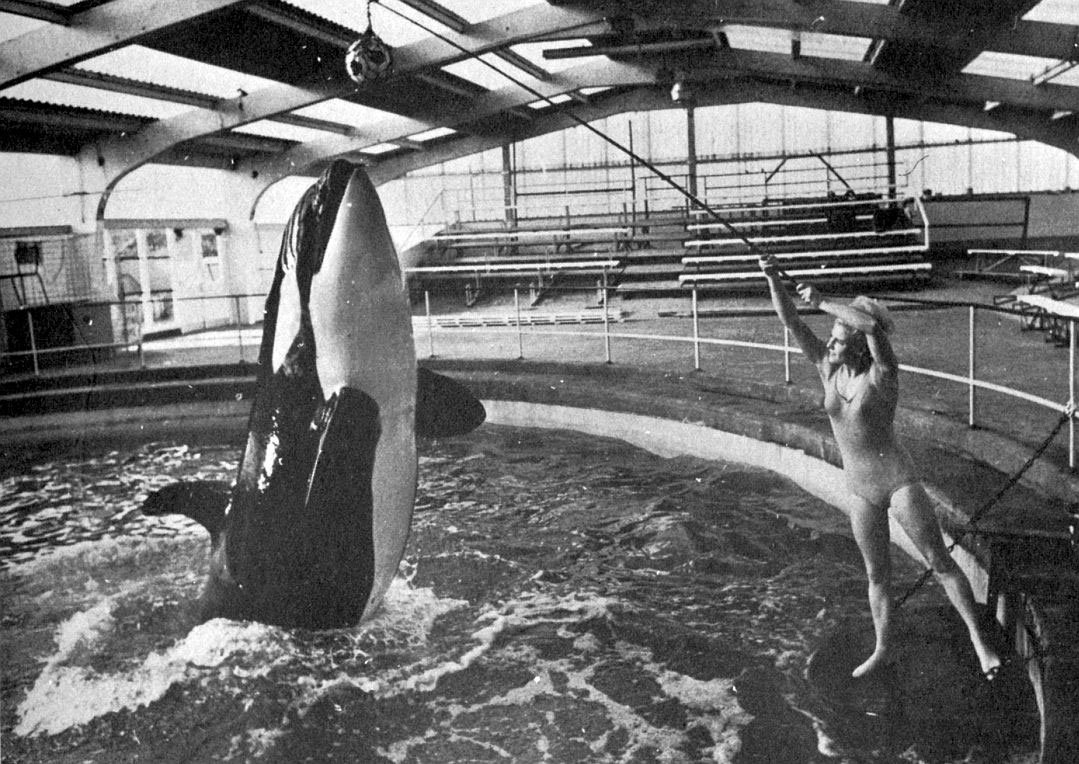

Η όρκα Cuddles στο τζακούζι της. Βλ. Cetacean Calling.

Willy the Whale Car Wash (1983). Βλ. Agenbyte.

Willy the Whale Car Wash (1983). Βλ. Agenbyte.

Το στρες μιας όρκας. Η όρκα Tilikum, ακίνητη και μόνη, στο πάρκο του SeaWorld. Η Tilikum έχει εμπλακεί έμμεσα ή άμεσα σε τρία θανάσιμα ατυχήματα. Βλ. The Orca Project.

Η απομονωμένη ζωή της Shouka, χωρίς συντροφιά, στο θαλάσσιο πάρκο Six Flags- Discovery Kingdom στην Καλιφόρνια. Βλ. The Orca Project.

Βλ. Orca Project.

Βλ. The Orca Project.

Βλ. The Orca Project.

Βλ. The Orca Project.

SeaWorld Orlando (Φλόριντα), Φλεβάρης του 2010. Η Dawn Brancheau, εκπαιδεύτρια με 16 χρόνια εμπειρίας, παρασύρεται μέσα στο νερό από την όρκα Tilikum και τραυματίζεται θανάσιμα. Μάρτυρας δήλωσε στο CNN ότι η όρκα πλησίασε τη γυάλινη πλευρά της δεξαμενής και άρπαξε την εκπαιδεύτρια από τη μέση τιναζοντάς την βίαια. Η φωτογραφία τραβήχτηκε στο τέλος του σόου, λίγο πριν το τραγικό ατύχημα.

"Near death at Seaworld". 'Ενας εκπαιδευτής παρασύρεται από μία όρκα στον πάτο της δεξαμενής του θαλάσσιου πάρκου του Seaworld.

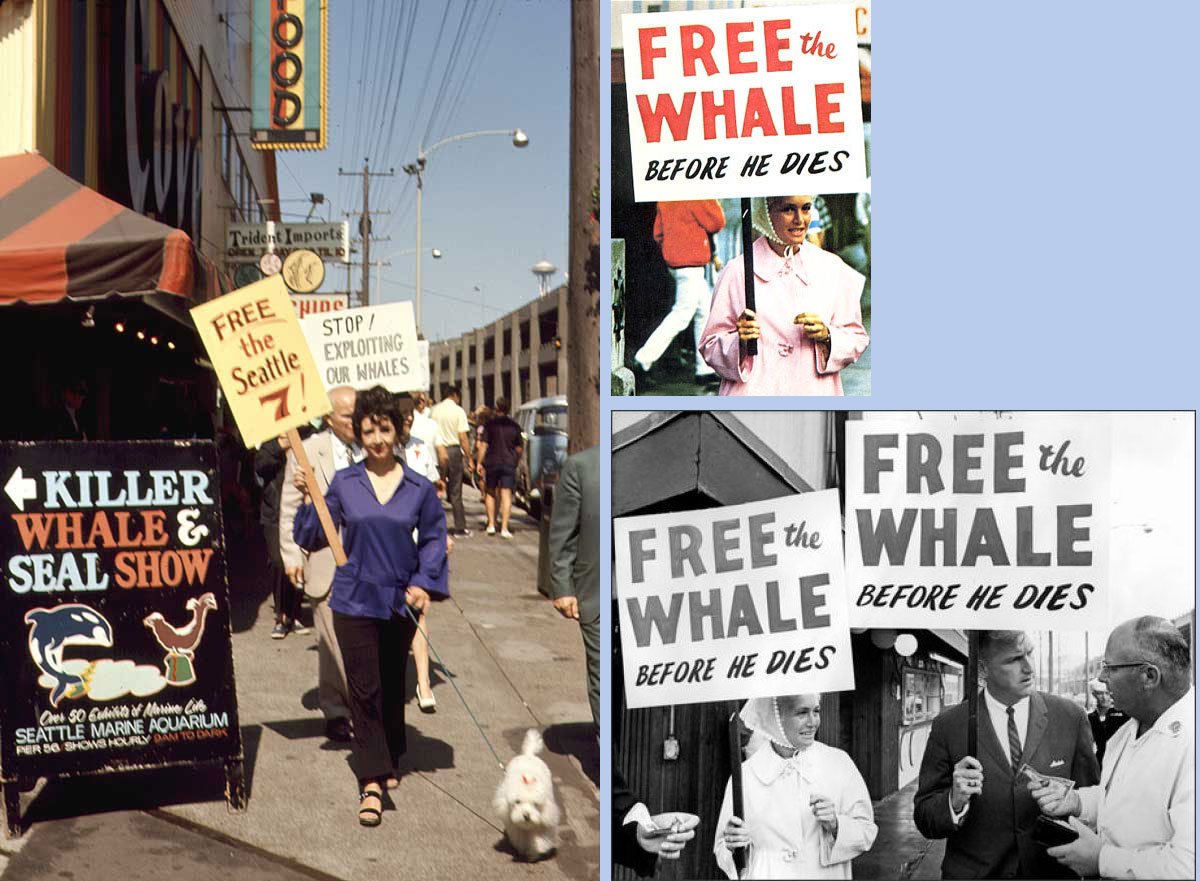

Διαμαρτυρίες στο Seattle το 1965 για την εκμετάλλευση θαλάσσιων ζώων σε πάρκα. Η όρκα Namu, σταρ του σινεμά πριν την Keiko στην ταινία Namu, the Killer Whale, δεν άντεξε πάνω από ένα χρόνο στις συνθήκες αιχμαλωσίας και πέθανε το 1966.

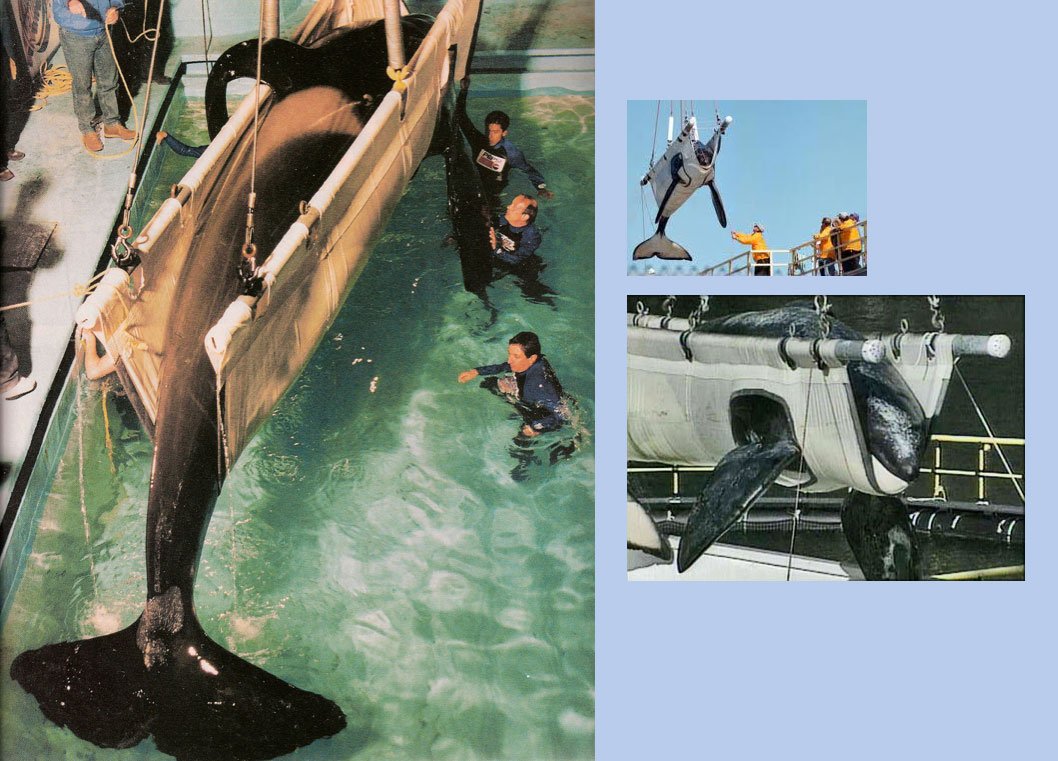

Η Keiko επιβιβάζεται στο αεροσκάφος που θα τη μεταφέρει στα νησιά Westman της Ισλανδίας. Φωτ. Master Sgt. Dave Nolan, USAir Force.

Η επανένταξη στην Ισλανδία.

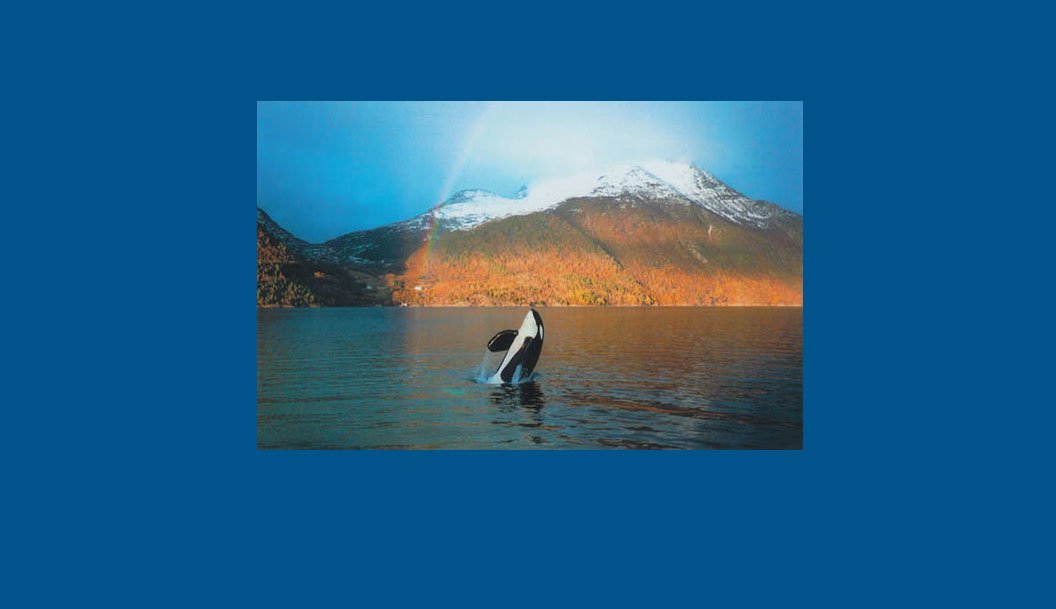

Η Keiko ελεύθερη στο ίδιο θαλάσσιο περιβάλλον όπου είχε γεννηθεί πριν πιαστεί αιχμάλωτη στα δίχτυα ψαράδων. Θα ζήσει ακόμη 5 χρόνια μακριά από τα θαλάσσια πάρκα, κάτω από την επίβλεψη της επιστημονικής ομάδας του ιδρύματος Free Willy Foundation, επιδεικνύοντες μεγάλες ικανότητες αναπροσαρμογής.

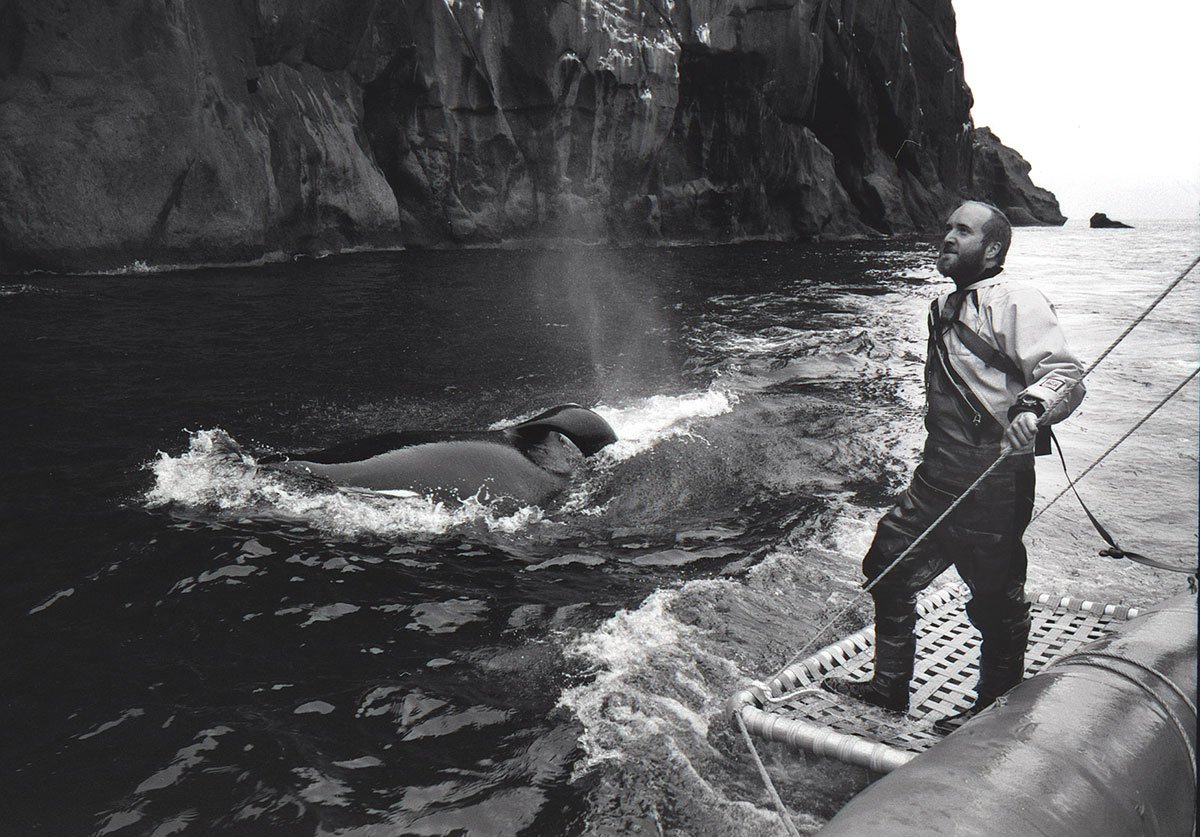

Ο Stephen Claussen παρακολουθεί την προοδό της Keiko στα νησιά Cliffs της Ισλανδίας. Ο Stephen Claussen ήταν ο εκπαιδευτής της Keiko στη διάρκεια των γυρισμάτων της σειράς Ελευθερώστε τον Γουίλι. Αργότερα συνεργάστηκε με την Free Willy Foundation. 'Ηταν στο αεροπλάνο που μετέφερε το 1998 την Keiko στην Ισλανδία. Σκοτώθηκε το 2008 στη συντριβή ενός μικρού Cessna σε περιοχή του New Jersey, καθώς ερευνούσε τις επιπτώσεις των ανεμογεννητριών πάνω σε θαλάσσια θηλαστικά και πουλιά.

Ο Stephen Claussen και η ομάδα της Ισλανδίας. Φωτ. Ocean Futures Society.

Stephen Claussen. Φωτ. Chuck Davis.

Στην γαλλική ταινία De rouille et d'os (Σώμα με σώμα) του Jacques Audiard, που παίζεται αυτές τις μέρες, η Marion Cotillard υποδύεται μία εκπαιδεύτρια σε θαλάσσιο πάρκο.

Ο Jean-Michel Cousteau (γιος του Jacques Cousteau), εξετάζει μία όρκα. Φωτ. Carrie Vonderhaar, Ocean Futures Society.

Ethical Debate: Should we have freed Willy?

By David Shiffman, on April 29th, 2010.

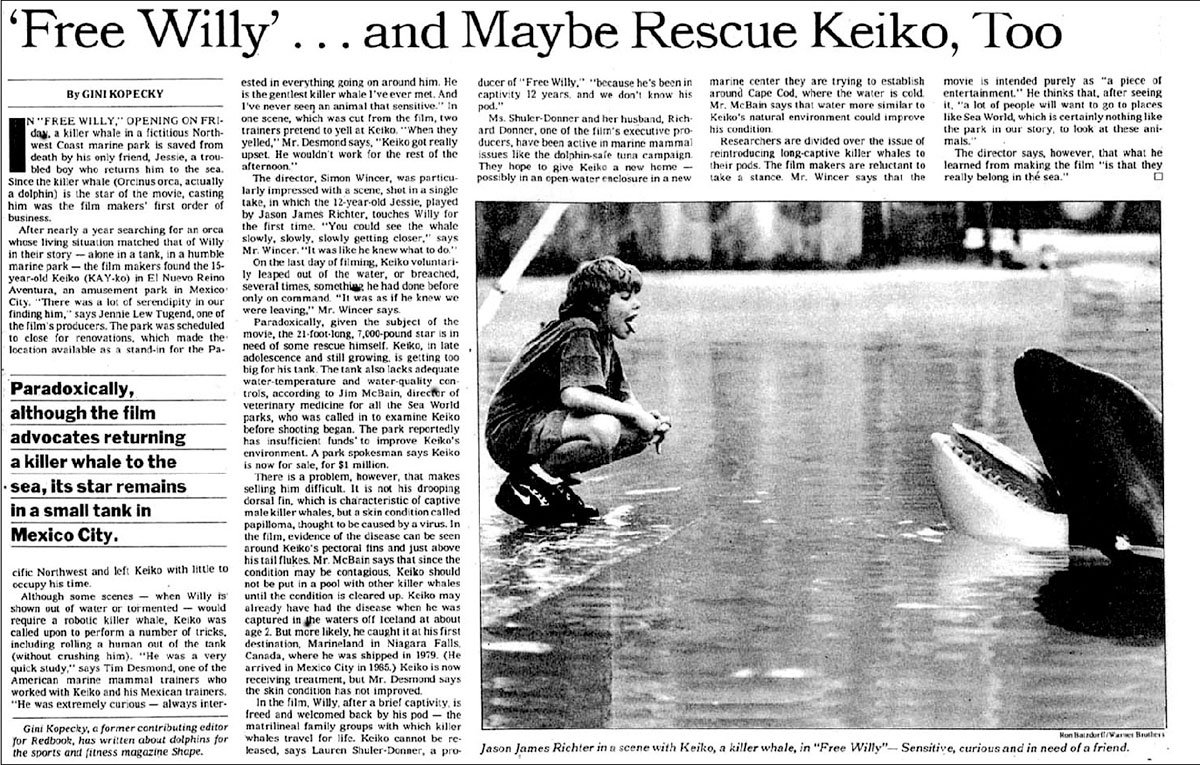

The death of Sea World trainer Dawn Branchaeu revived an old debate over whether it is appropriate to keep orca whales in captivity. Many people are calling for all captive orcas to be set free, but I continue to support aquariums because of the roles they serve as educators and conservationists. Although several readers have pointed out that the sea world incident itself would make for a solid ethical debate, I am instead going to take you back more than 15 years to a movie that started this whole movement: Free Willy.

The movie chronicles the adventures of a boy who works at an aquarium, where he befriends a captive orca whale. Because the whale is sad in captivity, he eventually frees it. After the success of the movie, there was a real-life campaign to free Keiko, the whale who played Willy in the film. Unlike in the movies, however, an animal that is used to being fed in an aquarium can't just be set free in the wild- it needs to be reacclimated. This was done with Keiko, and it is chronicled in the Cousteau film "Call of the Killer Whale" and on Keiko.com. Jean-Michel Cousteau, President of the Ocean Futures Society, kindly agreed to answer my questions about this fascinating story. I believe that the lessons learned from releasing Keiko can help us decide what to do about currently captive orca whales.

WhySharksMatter (WSM): Tell me the story of rehabilitating and releasing Keiko the Whale.

Jean-Michel Cousteau (JMC): In 1993, the "Free Willy" film was a surprise hit and that, combined with press coverage detailing Keiko's poor health and inadequate living conditions in Mexico City, created a groundswell of support, particularly from children throughout the world, for his release, to live up to the spirit of the film. In response, Earth Island Institute negotiated with the Oregon Coast Aquarium for his rehabilitation and the Free Willy Foundation was formed with a donation from Warner Brothers, a donation from the Humane Society of the U.S., money from a then-anonymous donor, the donation of Keiko by Reino Aventura, and unsolicited money sent in by children from around the world.

WSM: What was the source of the idea to free Keiko? Why did you all think that releasing Keiko was the right thing to do?

JMC: The source of the idea was public outcry from the film, not only on the issue of captivity but because Keiko was in such poor health and in such poor conditions, living in artificial seawater, 7,200 feet above sea level, breathing smoggy air, cramped in a small pool, and swimming in circles to entertain the crowds. It was clear that if Keiko were to survive, he had to be moved. It was not a project that anyone would have taken on as an experiment, but it became the only humane thing to do, especially under such public outrage and scrutiny.

WSM: Do you think it's fair to other orcas that Keiko was chosen based on his celebrity from "Free Willy" while they remained captive?

JMC: As described above, Keiko was not "chosen" above other captive whales, but his celebrity was key in attracting attention to his poor health and bad conditions. The issue was less one of captivity in general and more about doing something to save this one specific whale.

WSM: Advocates for aquariums (such as myself) often argue that while the life of an individual animal may be worse in captivity than in the wild, having captive animals helps the species as a whole by promoting education and conservation to the public. What do you think about this?

JMC: The elation we feel in the presence of such a magnificent animal should not be used to justify the destructive assumption that we have the right to imprison these animals for our pleasure. That is a dangerous assumption and leads to the belief that all of nature is for our pleasure and we have the right to manipulate it. That is anti-educational. We need to educate people to cherish and respect animals and places they may never see or touch because they are a vital part of our own survival.

WSM: How did Keiko react after being released? How long did he live?

JMC: It is important to make the distinction that it was not the intent to "release" Keiko, but rather to "reintroduce" Keiko to the wild. These are not mere semantics. In order to live in the wild, Keiko had to re-learn to live with a pod of orca and be accepted by a pod. He had to learn to catch his own wild food. And to survive, he had to learn to hunt with a pod, sharing the food caught for all by the family unit. This was a learning process for Keiko and for his care givers and trainers. It was a slow and methodical process over more than three years during which Keiko spent increasing amounts of time with wild whales. During the fourth summer, he spent all his time in the wild, catching his own food and swimming adjacent to wild whales. Was he truly accepted? We will never know; we can only observe that he ate with them, lived near them and was free in the wild. He joined them in swimming away from Iceland. He traveled more than 1000 miles in the open ocean over three weeks to Norway, arriving in good health without losing any weight during more than 10 weeks on his own. Thereafter, he lived freely, with free choice to come and go as he wanted in a fjord in Norway. Caretakers provided food because there was not a ready supply of wild food and because wild orca did not come into the fjord regularly.Keiko died of a respiratory ailment in the winter of 2003 at the age of approximately 28 years, the oldest male whale that had been in captivity. His final five years were spent in ocean conditions and he lived his final years swimming free with caretakers nearby to provide sustenance and companionship. In a nutshell, what we have all learned from this experience is how easy it is to capture a whale (or any living creature) and how difficult it is to put one back.

WSM: How much total money went into rehabilitating and releasing Keiko? How many people were involved? How long did it take?

JMC: This effort was initiated and carried out because so many people at Warner Brothers, Earth Island institute, the Humane Society of the U.S., the Free Willy Keiko Foundation, and Ocean Futures Society felt a deep responsibility both to Keiko and to the children of the world who demanded his rehabilitation and return to the wild. Donations were evidence of the commitment of tremendous resources to an idea and an ideal. More than $40 million was expended to create facilities in the U.S. and Iceland, hire and train staff, transport Keiko and care for him over the more than eight years after his move from Mexico to Newport, Oregon, and then to Iceland/Norway.More than 75 people were directly involved, many for almost the full eight years, dedicated by their hearts and the joy of children everywhere.

WSM: Do you think it was appropriate to spend so much time, money, and effort helping an individual whale instead of on species or ecosystem level cosnervation?

JMC: That was never a choice. Hundreds of people and millions of dollars were spent in response to saving this one unique whale in unpredictable and unprecedented circumstances. I do think that the exorbitant cost of rehabilitating, retraining and releasing Keiko taught us that this is not an option to be considered with other captives unless we know exactly the pod they belong to and that they could be reunited. Since most of those whales have been in captivity a very long time, it would be an experiment of hope and undertaken with caution.

WSM: Given your experiences with Keiko, do you feel that rehabilitating and releasing more captive orcas is feasible?

JMC: For the reasons stated above, no, unless there are special circumstances and ample funding and expert personnel. I do believe we must take care of these captives for the rest of their lives and prevent them from reproducing. The cost could be borne by letting the public see them and be assured they are well cared for, but without any of the entertainment aspect. They are temporary ambassadors and we should study them in the most humane way and with the greatest intelligence we can muster.

WSM: In the wake of the recent tragedy at Sea World, many are saying that all captive orcas need to be freed. What do you think about this, both ethically and logistically? What do you think happened in that situation?

JMC: For the reasons above, I do not think all captives can be successfully returned to the wild and it would be cruel to simply release them, almost certainly dooming them. Ethically, we need to care for them for the rest of their lives and prevent any future captures or breeding programs. We will never fully understand the incidents at Sea World other than that they are tragic.

WSM: Tell me about the Ocean Futures Society.

JMC: The mission of Ocean Futures Society is to explore our global ocean, inspiring and educating people throughout the world to act responsibly for its protection, documenting the critical connection between humanity and nature, and celebrating the ocean's vital importance to the survival of all life on our planet. Membership is free at www.oceanfutures.org

WSM: Is there anything else you'd like to say about this subject?

JMC: We must remember that we are a young species and we are still learning about the world around us. Without creating enemies, we need to move on from the captive orca industry which is appearing more and more barbarian in that we engage in what I think we will see as unethical, cruel and unwarranted ways to contain these animals for our pleasure. No amount of research or disputed educational value warrants these acts. It is time for us to change and to move on and create new, healthier, more respectful bonds with the natural world. It is the only way we will save ourselves.

Keiko, Halsa, Νορβηγία. Φωτ. Mark Berman.

KEIKO'S STORY: THE TIMELINE.

(Free Willy - Keiko Foundation).

This is the story of how a two-year-old orca whale began an amazing journey that has spanned five countries and tens of thousands of miles.

1977 or 1978:

Keiko is born in the Atlantic Ocean near Iceland.

1979:

Keiko is captured by a fishing boat, separated from his family, and held in an Icelandic aquarium.

1982:

Marineland in Ontario, Canada buys Keiko, where he becomes a performing animal.

1985:

Marineland sells Keiko to Reino Aventura, an amusement park in Mexico City, for $350,000.

1992:

Warner Bros. Studios begins filming the movie "Free Willy" on location in Mexico City. The plot involves a young boy saving a whale, portrayed by Keiko.

1993:

Free Willy is a surprise hit at the theaters, especially with millions of school children around the world. That support, along with media coverage detailing Keiko's unacceptable living conditions in Mexico City, prompts the movie studio, the park, and animal protection advocates to find Keiko a new home. Dr. Lanny Cornell comes on board as Keiko's lead veterinarian.

1994:

Earth Island Institute, an environmental advocacy group for marine wildlife, begins the search for a location where Keiko can be brought back to health and trained for potential release to the wild. The Free Willy Foundation is formed in November with a $4 million donation from Warner Bros., and an anonymous donor.

1995:

The Mexico City amusement park donates Keiko to the Free Willy/Keiko Foundation. The foundation announces Keiko will be moved to a new, $7.3 million rehabilitation facility at the Oregon Coast Aquarium. Craig McCaw is revealed as the anonymous donors of $2 million, which helped start the Free Willy/Keiko Foundation. The Humane Society of the United States also becomes a sponsor.

1996:

United Parcel Service sponsors the airlifting of Keiko to the aquarium on January 7. Weighing just 7,720 pounds, Keiko is placed in his new pool and experiences natural sea water for the first time in 14 years. Keiko gains more than 1,000 pounds, and by year's end his skin lesions begin to heal. Keiko is featured on the cover of Life Magazine and in a popular documentary, The Free Willy Story, on the Discovery Channel. More than 2 million visitors come to see Keiko in Oregon.

1997:

Keiko's staff begins introducing him to live fish in an effort to teach him to hunt for food. His skin lesions have all disappeared and he is determined to be in excellent health. He catches and eats his first live fish in August. By June, Keiko weighs 9,620 pounds. The staff of the Free Willy/Keiko Foundation sets a goal of releasing Keiko into a pen in the North Atlantic by 1998. After an intensive search and negotiations with foreign governments the decision is made to reintroduce Keiko to the wild in Iceland.

1998:

A medical panel determines that Keiko is healthy and exhibiting the normal behavior patterns of a killer whale. Keiko is eating live steelhead weighing from three to 12 pounds each, comprising up to half of his daily intake of food. On September 9, Keiko is lifted from his tank and transported by a US Airforce C-17 transport jet from Newport directly to Klettsvik Bay in Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland.

1999:

During his first full year back in his native Icelandic waters, Keiko, now under the day-to-day care of the Ocean Futures Society, continues training to prepare him for his potential reintroduction to the wild. An essential component of his program is moving his attention from above to below the surface of the water. In doing so, Keiko depends less on his human caretakers and develops greater interest in his natural environment.

2000:

Keiko is fitted for a tracking device that will allow staff to take him out to the open ocean. Keiko makes amazing progress during his sea "walks," even beginning to interact with wild orcas in the vicinity of his sea pen. His health and stamina improves as he comes closer to returning to his wild ways.

2001:

Early in the year, Keiko exhibits behaviors consistent with wild whales-competing with other animals for food. Keiko begins initiating contact with wild orcas in the vicinity and spends several days away from his human companions. The primary challenge ahead is for Keiko to begin maintaining himself on wild fish and regularly associating with wild orcas.

2002:

On his first day out of the netted bay pen in the summer of 2002, Keiko leaves the tracking boat and begins spending considerable time in the company of whales. He is monitored in and around groups of wild whales for the next three weeks. He then begins an epic journey covering nearly 1000 miles across the North Atlantic, by the Faeroe Islands, and to the coast of Norway.The first observations of Keiko in Norway document that he is in excellent physical condition. Keiko has been on his own for close to 60 days without food from humans. His lead veterinarian, and a variety of other orca scientists, come to the conclusion that Keiko has successfully fed himself in the wild, a major milestone in his journey to the wild.

Keiko follows a fishing boat inside a Norwegian fjord in the Halsa Community. He is an instant hit there with people coming from throughout Europe. Thousands of visitors come to see the friendly whale. The Project staff work closely with the Norwegian government to put in place regulations to keep people from swimming with, feeding, or getting too close to Keiko.

Meanwhile, the Craig McCaw Foundation and Ocean Futures Society turn over the management of the project to the Free Willy Keiko Foundation and the Humane Society of the U.S.

In December Keiko is walked to the Taknes bay staff continue to work with and feed Keiko. For the first time ever, Keiko is in an area where he can come and go as he chooses. The Free Willy Keiko Foundation and the Humane Society of the US continue to care for Keiko while allowing his historic journey to the wild to move ahead.

The Norwegian government gives its full support to the continued effort to give Keiko the chance to return to the wild.

2003:

December 12, 2003 -- The Free Willy Keiko Foundation and The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) reported today that Keiko, the orca whale, died today in the Taknes fjord, Norway, in the company of staff members who have been caring for him there.

Keiko's veterinarian believes that acute pneumonia is the most likely cause of death, though he also cited that Keiko was the second oldest male orca whale ever to have been in captivity.

The two organizations managing Keiko's reintroduction effort expressed sadness at Keiko's death while also heralding his amazing journey.

Yesterday, Keiko exhibited signs of lethargy and lack of appetite. Consultation was continuous between his caretakers and Dr. Cornell. His behavior was still abnormal this morning and his respiratory rate was irregular, but, as is often the case with whales and dolphins in human care, these were advanced signs of his condition. With little warning, Keiko beached himself and died in the early evening local time. A decade ago, Keiko was featured in the Hollywood movie, Free Willy, prompting a worldwide effort to rescue him from poor health, in an attempt to allow him to be the first orca whale ever returned to the wild.

In 1996 Keiko was flown aboard a United Parcel Service plane to a new rehabilitation facility in Newport, Oregon. There he was returned to health and trained in the skills necessary to be a wild whale. In late 1998, Keiko was flown in a U.S. Air Force jet to a sea-pen in Iceland. In the summer of 2002, Keiko joined the company of wild whales and swam nearly 1000 miles to the Norwegian coast. Since then, Keiko has been cared for in a fjord where he was free to come and go by his own choice.

Keiko inspired millions of children to get involved in following his amazing odyssey and helping other whales. Keiko's journey also inspired a massive educational effort around the world and formed the basis for several scientific studies. Thousands of people traveled to Norway in the past year to see Keiko, continuing his legacy as the most famous whale in the world.

σχόλια