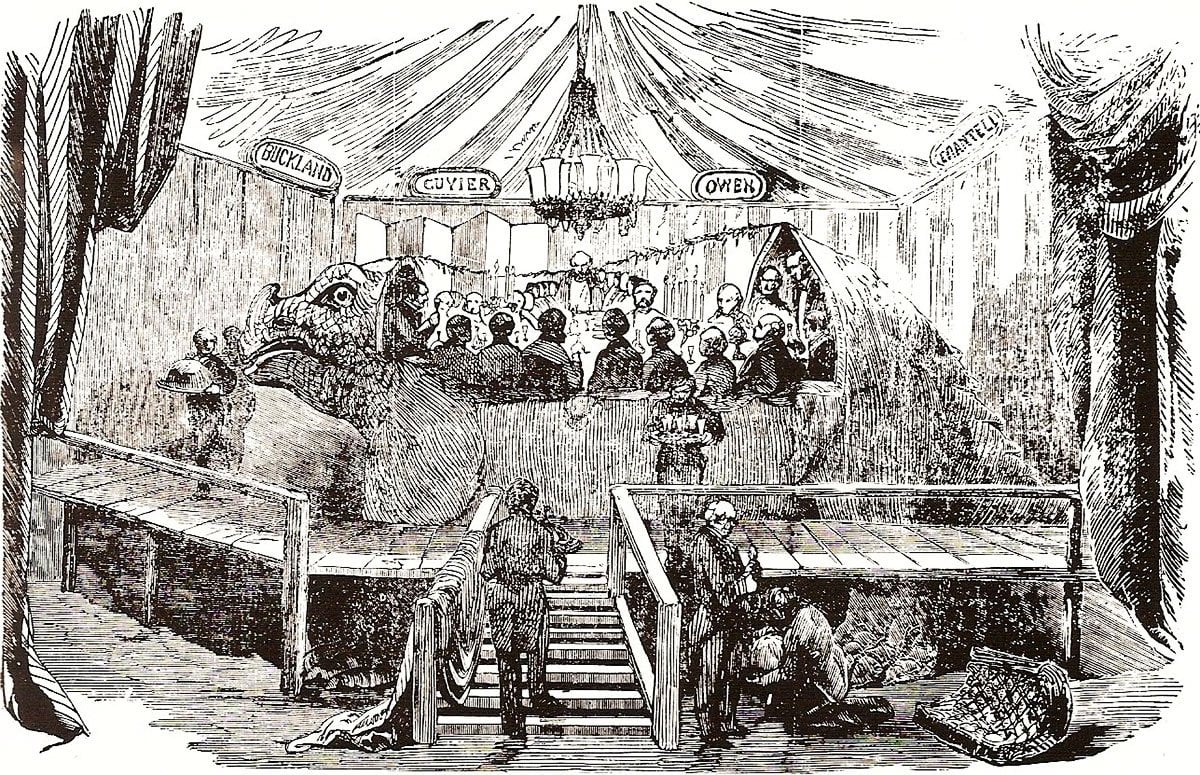

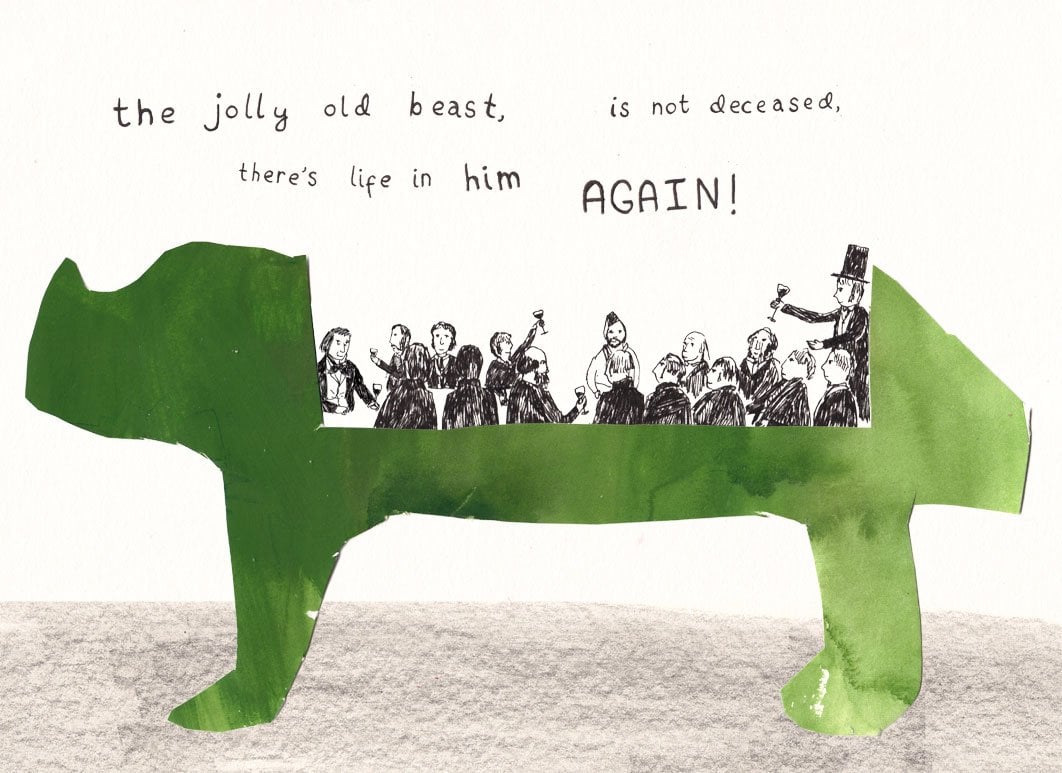

London Illustrated News (1854 - από το βιβλίο The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs των Steve McCarthy και Mick Gilbert).

London Illustrated News (1854 - από το βιβλίο The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs των Steve McCarthy και Mick Gilbert).

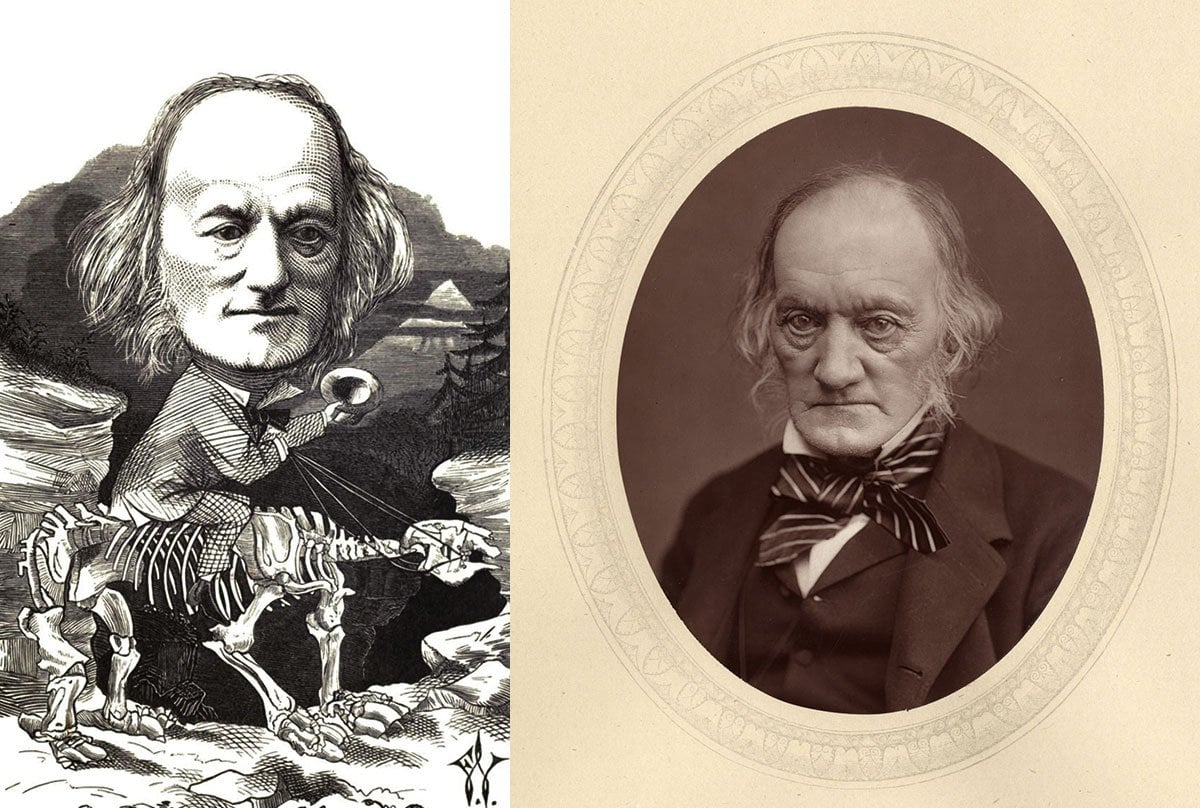

Διευθυντής από το 1856 του Natural History Museum του Λονδίνου, που αναδιαρθρώθηκε και αυτονομήθηκε από το British Museum με δική του πρωτοβουλία, ο Sir Richard Owen είδε την καριέρα του να αμαυρώνεται από διάφορες υποθέσεις λογοκλοπής. Στην περίπτωση ειδικά του παλαιοντολόγου, και αιώνιου εχθρού του, Gideon Mantell, δεν δίστασε να επωφεληθεί της αρρώστιας του τελευταίου για να οικειοποιηθεί το έργο του και να το διαστρεβλώσει. Βλ. πιο κάτω σχετικό άρθρο στο μπλογκ The Study.

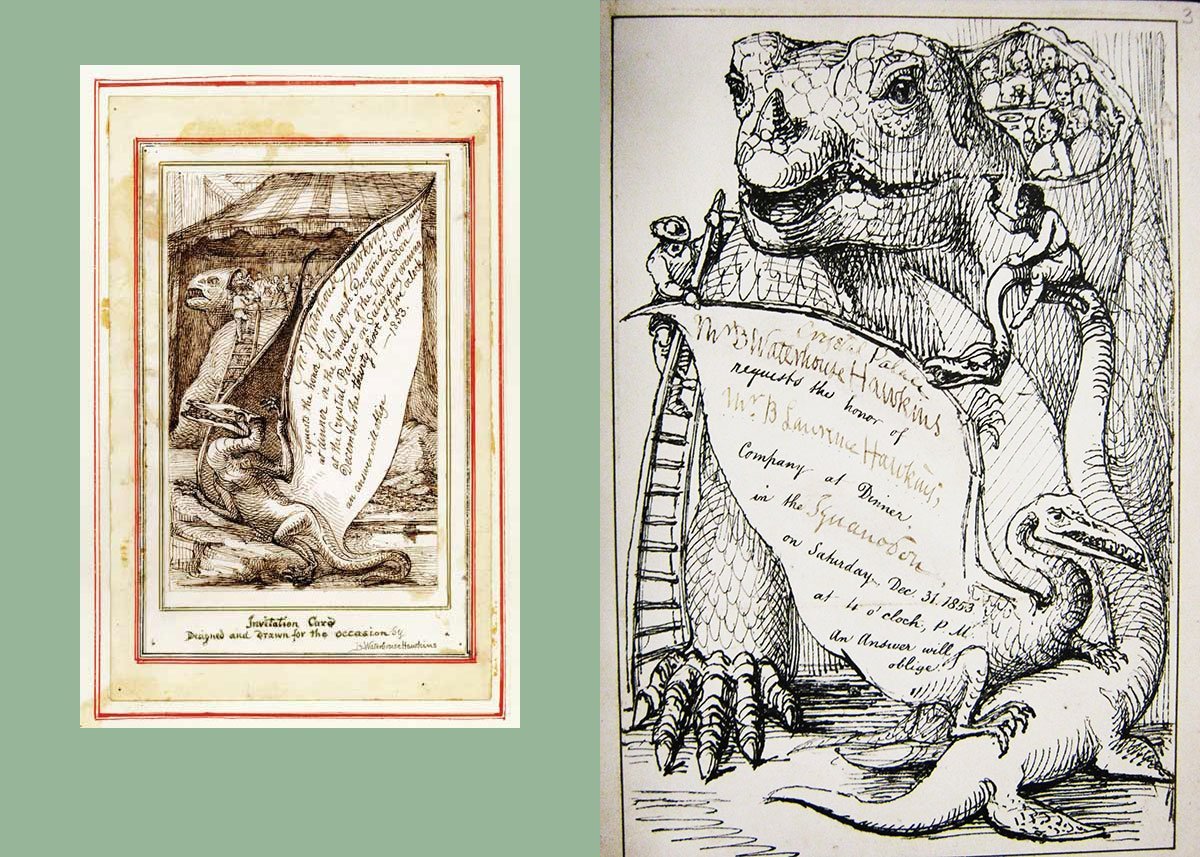

Η πρόσκληση για το ρεβεγιόν. Ewell Sale Stewart Library of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Βλ. Cabinet Magazine, Brian Selznick και David Serlin, A Buried History of Paleontology.

Αριστ. : "Ο Richard Owen καβάλα στο χόμπι του (Megatherium)". Καρικατούρα του Frederick Waddy (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Βλ. Wikipedia.

Δεξ. : βλ. Natural History Museum.

Ο Sir Richard Owen.

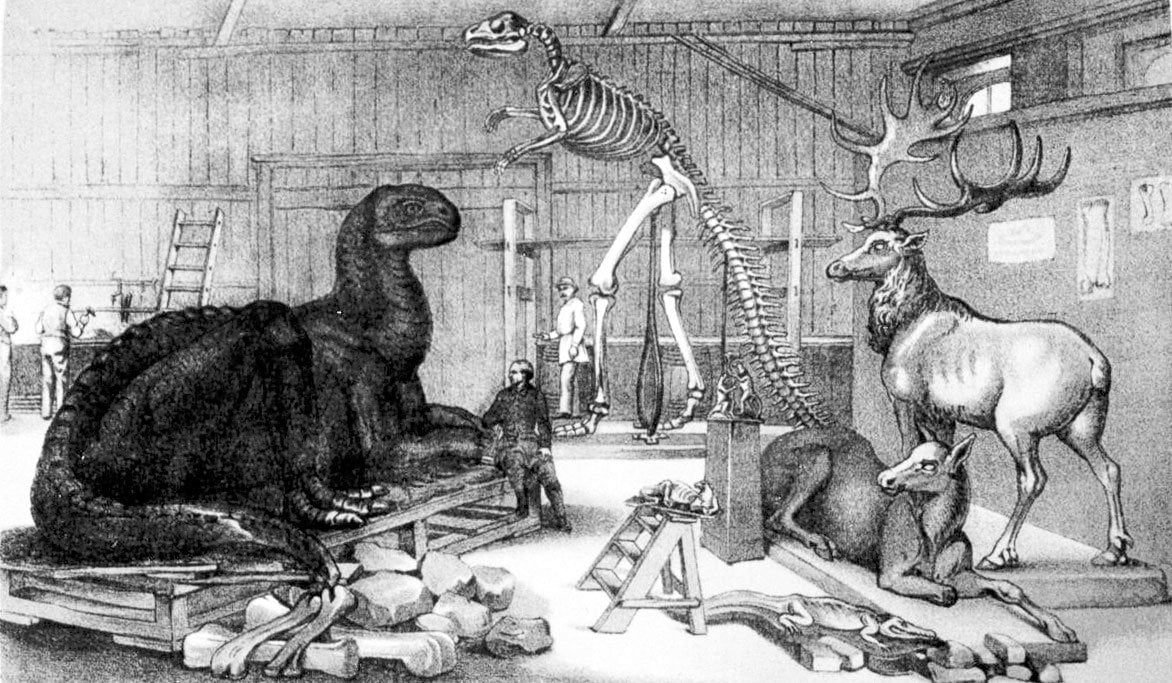

Αριστ. : Το εργαστήρι του γλύπτη Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins στο Sydenham, όπου κατασκευάστηκαν οι δεινόσαυροι του Crystal Palace. Via David Goldman, Paleontology and Politics. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and his New York City Paleozoic Museum.

Δεξ. : Ο ίδιος ο Hawkins κάτω από μία δική του κατασκευή.

Crystal Palace Prehistoric Animals, σχέδια του Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. Johnson's Natural History, 1871.

Βλ. David Goldman, Paleontology and Politics. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and his New York City Paleozoic Museum.

Το εργαστήρι του Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins.

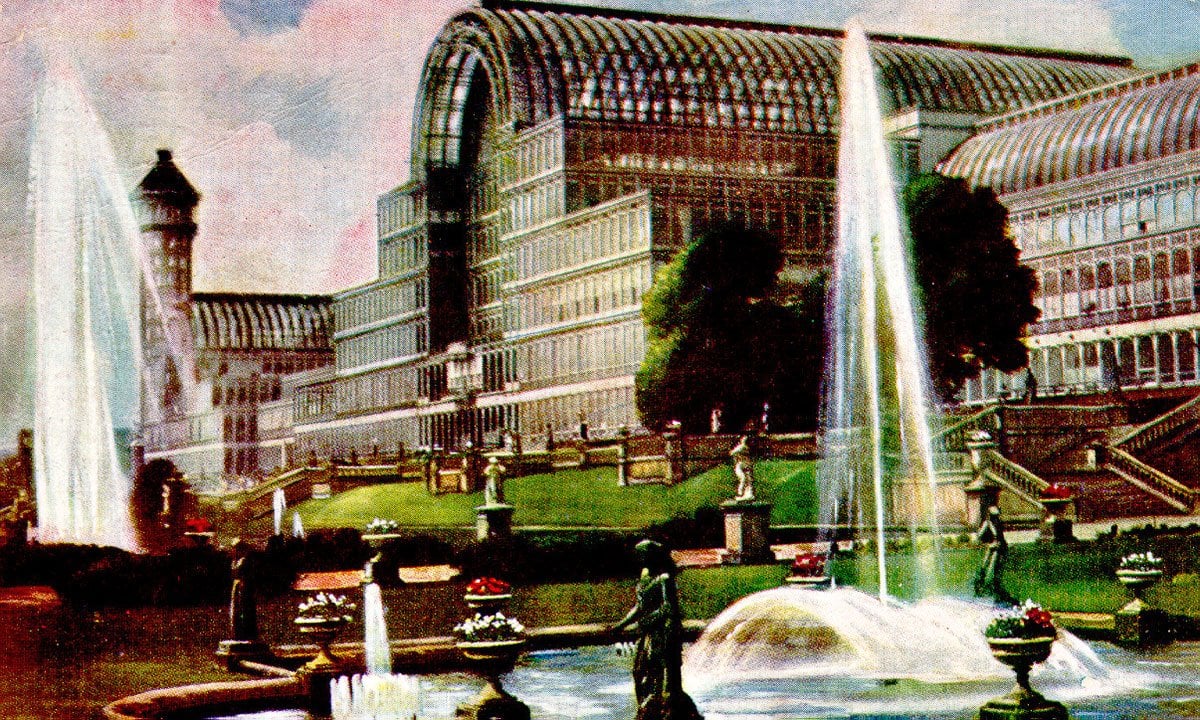

Το Crystal Palace του Λονδίνου όπου πραγματοποιήθηκε η Μεγάλη 'Εκθεση του 1851. Εκεί παρουσιάστηκαν για πρώτη φορά οι δεινόσαυροι του Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins.

Το Crystal Palace. Το 1936, μία πυρκαγιά κατέστρεψε ολοσχερώς το κτήριο.

Η έκθεση στο Crystal Palace. Βλ. About. com, 19th Century History.

Η έκθεση στο Crystal Palace. Βλ. About. com, 19th Century History.

Σχέδιο του Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins για την 'Εκθεση στο Crystal Palace.

Το Νησί των Δεινοσαύρων στο Sydenham Park που φιλοξενεί σήμερα τους δεινοσαύρους του Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins.

Βλ. Mark Ryan.

Φωτ. Εxtremegroundhopping.

Φωτ. Εxtremegroundhopping.

Λανθασμένη απεικόνιση του ιγκουανόδοντα ως τετράποδο από τον Richard Owen, ενώ ο Gideon Mantell είχε υποθέσει σωστά από το 1825 ότι επρόκειτο για δίποδο δεινόσαυρο.

Φωτ. Εxtremegroundhopping.

Σχέδιο του Joe Lyward (2012).

The Study

Sunday, 26 August 2012

The Dastardly Doings of the Palaeolographical Professor

Posted by Michael Hartley.

You might imagine that Richard Owen would have been one of history's Good Guys – he had the advantage of being born in Lancashire, which automatically blessed him with one of life's greatest benefits, and in later life he championed the opening of the Natural History Museum at Kensington to the general public, when the general consensus of the scientific community was that entry to museums should be solely reserved for specialist scholars.

When, as a teenager, he was training as an anatomist in Lancaster, he started a collection of mammal skulls – dogs, deer, mice, cats and so on – and when he was present at the post mortem of a black prisoner who had died in Lancaster Gaol, he determined to procure the dead man's skull to add to his collection. Armed with a stout brown paper sack and swathed in a heavy black cloak, he returned to the dissection room in Hadrian's Tower at Lancaster Castle after dark, got the keys and a lantern from the turnkey and locked himself in, using the instruments in the room to detach the head. Hiding his grisly trophy in the sack beneath the folds of his cloak, he tipped the wink to the turnkey and made his way out of the prison and into the night.

Now, at the bottom of the hill below the castle, there was a cottage that had once belonged to a former slaver, who had died in a bar fight, and where his widow and daughter still lived. That night, by the light of the fire, they were telling tales of the slave trade, when suddenly there was a thump at the door, which burst open and there, in the glow of the firelight, they saw the whites of a black man's eyes staring up at them. They screamed and tried to run, when a man cloaked in black erupted into the room, snatched up the black man's head and disappeared into the dark. The Devil, it seemed, was abroad in Lancaster that night and had come for his own. In reality, Owen had slipped on the slick ice on the cobbles and dropped his prize, which had rolled down the hill and in through the cottage door. Owen ran after it, grabbed it from the floor and departed as quickly as he had arrived, running for home as fast as his legs would bear him.

Owen went on to study medicine at Edinburgh and London, but his work at the Royal College of Surgeons confirmed his interest in scientific research and he went on to become Professor at the Hunterian museum. He published numerous academic studies on comparative anatomy and built a formidable reputation throughout Europe as an expert on palaeontology and fossil identification. His first published work, Memoir of the Pearly Nautilus (1832), was an instant classic, and over the next fifty years he went on to make enormous contributions to all areas of anatomy and palaeontology. He was the automatic choice to study the fossils brought back from South America by Charles Darwin on The Beagle in 1836, and it was Owen's identification of the mammals as rodents and sloths related to existing smaller species still found on the pampas that lead Darwin to re-evaluate his earlier speculations that they were related to the larger African mammals, an important step in his formulation of the theory of evolution by natural selection.

The Sydenham dinosaurs - Punch 1855

One of Owen's odder projects was as advisor on the construction of the model dinosaurs (a word first coined by Owen) for the Great Exhibition of 1851 (better known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition). In collaboration with the sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, thirty-three life-size dinosaurs were produced and were moved to Sydenham when the Crystal Palace was moved there, Owen famously hosting a dinner party for twenty-one distinguished guests inside the unfinished model of the iguanodon on New Year's Eve 1853.

The figures were built from concrete and steel and fell into great disrepair over the years until they were restored, starting in the 1950s and given Grade 1 Listed Status in 2007, in spite of being now regarded as out of date and wildly inaccurate. All well and good then – Owen sounds like he really was one of the Good Guys.

Except – he wasn't.

As we have seen in his treatment of Gideon Mantell, he was not above claiming the credit for the work of others – he wrote that it was he and Cuvier who had discovered the iguanodon, rather than the real discoverer - Mantell.

He also identified the horny thumb of the iguanodon as a horn, and it was placed on the head of the iguanodon figures at Sydenham, as well as having the creatures depicted as bulky quadrupeds rather than the more gracile bipeds they actually were (and as which Mantell had identified them).

In 1844, Owen presented a paper to the Royal Society on fossil belemnites for which he was presented with the Society's Gold Medal in 1846, but he forgot to mention the work of an amateur biologist, Joseph Channing Pearce, who had discovered the belemnite (a type of Mesozoic marine cephalopod) in 1842, and had presented his own paper at a meeting of the Society at which Owen had been present. In the scandal that followed, Owen was voted off the councils of the Royal Society and the Zoological Society, but his plagiarism didn't stop there. He used illustrations from Mantell's works and passed them off as his own, and only grudgingly apologised when he was found out.

Owen was initially on good terms with Charles Darwin but their relationship soured over the years and Owen was the only person whom Darwin was known to hate. In a repeat of his 'anonymous' memoir of Mantell, Owen published an 'anonymous' review of Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) in the Edinburgh Review (1860) which was highly critical of the book and the theory, but fulsome in its praise for Professor Owen and his works (from which he freely quotes), but adds with grudging praise that some of Mr Darwin's observations on the varieties of pigeons are the 'real gems' of the opus.

In preview copies of The Origin, Owen had noted that Darwin's use of the terms 'I think' and 'I am convinced' were unscientific but urged him to retain them as they added to the overall charm of the work, then, when the book was published, he vocally attacked Darwin for using such unscientific terms as 'I think' and 'I am convinced'. In retaliation, Darwin wrote, "I used to be ashamed of hating him so much, but now I will carefully cherish my hatred & contempt to the last days of my life." In a letter to Asa Gray dated June 8th 1860, he wrote "... no one fact tells so strongly against Owen, considering his former position at the College of Surgeons, as that he has never reared one pupil or follower."

In 1857, Thomas Henry Huxley (popularly known as Darwin's Bulldog) was leafing through Churchill's Medical Dictionary when he noticed that a certain Richard Owen was listed as Professor of Comparative Anatomy and Physiology at the Government School of Mines, which was something of a surprise to him, as that was a position he held himself. He asked the editor of Churchill's how such a mistake could possibly have been made, and was told that the information had come directly from Professor Owen himself.

His lugubrious appearance in later life cannot have helped his cause – Bill Bryson calls his 'a face to frighten babies' – but he was almost universally disliked. His own son, William, who inexplicably committed suicide at the age of forty-nine, bemoaned his father's "... lamentable coldness of heart." One critic described him as "... a most deceitful and odious man," and after his death, an Oxford professor remembered him as "...a damned liar. He lied for God and for malice." As always, make up your own minds but in my opinion Professor Sir Richard Owen FRS KCB was an utter bounder and a frightful cad. So there.

σχόλια